Why Money Makes You Miserable 😭

Does it? Does having a pit full of cash make us sad? For many of us seeing this headline, it may sound completely counter-intuitive, considering the cost-of-living crisis that is currently hammering people’s lives.

Why would having financial security be a bad thing? It isn’t, my pedigree chums. In fact, as we’ve probably all read before, there is a sweet spot, a Goldilocks zone for our finances where we have enough to live, enough to do the occasional nice thing again, and enough to save for the future. And it makes us happy.

Beyond that point, however, our sense of well-being seems to plateau. We don’t seem to get happier the more money we have.

But in this newsletter I want to explore a slightly different idea: how the pursuit of money makes us miserable. Why worshipping at the altar of mo’ stuff, mo’ money, does not mean mo’ happiness.

Money and Happiness = Frenemies 🤼♂️

First, it’s worth looking at the data around how acquiring money doesn’t make us happy. The most complete research on this subject can be found in Edward Diener’s work on happiness and life satisfaction.

He looked at nearly 10,000 US-based adults over a nine-year period. In that group, he saw some of them experience huge increases in wealth, others modest, and some barely kept their head above water. What he expected was a nice neat graph where money increased, and so did happiness. But it was messy. Real messy. Earnings and assets it turned out were a poor indicator of happiness.

Philip Brickman, meanwhile, looked at what happened to happiness for those who won the lottery. He studied 22 winners of a local US lottery and compared them to a group of people who hadn’t. The result? The happiness of lottery winners was no different from that of the control group. That’s a lie. A significant number of winners reported lower life satisfaction after winning big bucks.

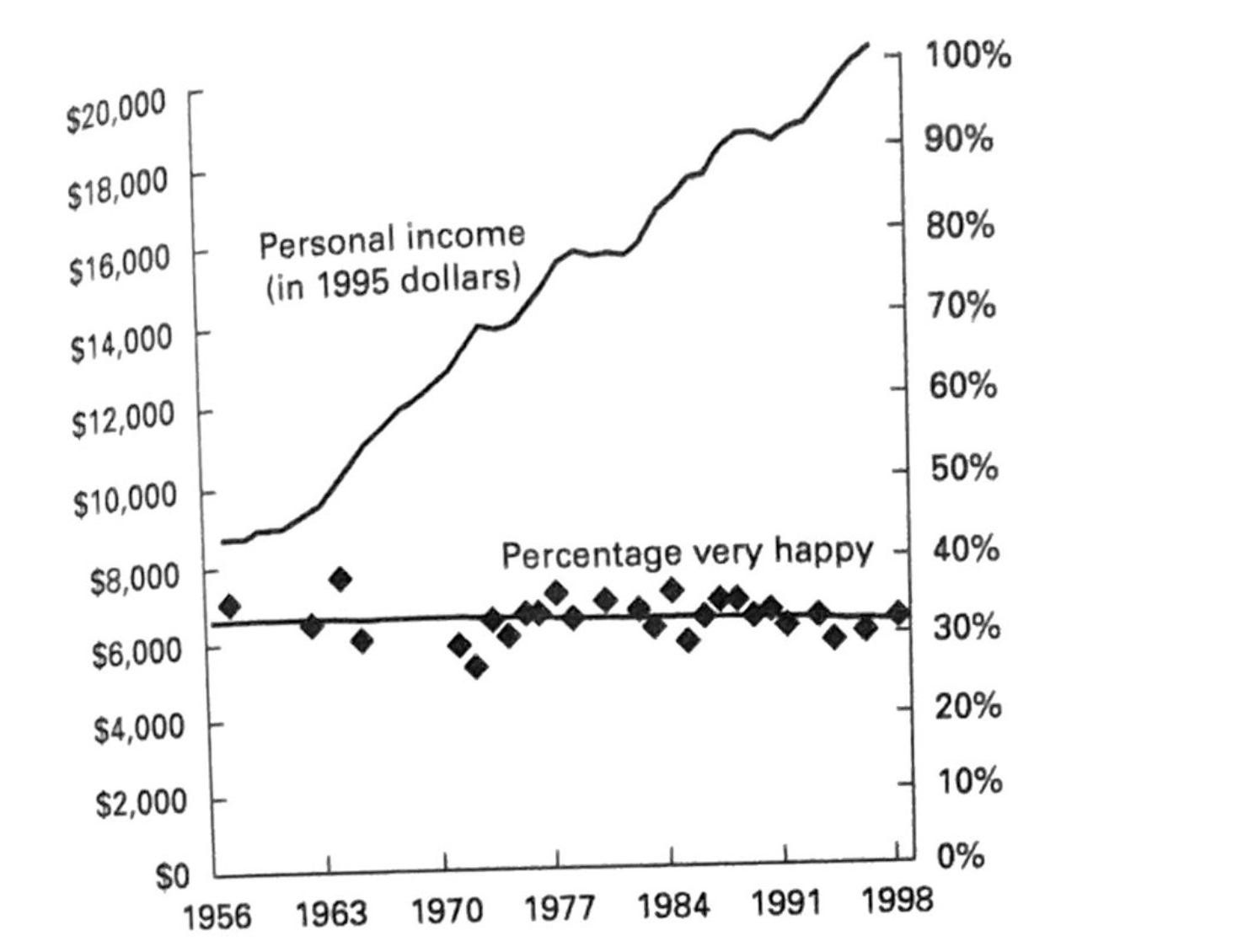

Another one? Sure. David Myers tracked happiness against GDP in America over the second half of the 20th century. As the American economy, and everyone in it, had more money - relatively speaking - happiness remained stubbornly unmoved. To put into perspective, people’s income doubled between 1956 and 1998, but their happiness stayed where it was. Illustrated by my terrible scan of a chart.

So now that we know that increases in wealth do not give us happy lives, it’s time to ask why.

It does it for four broad reasons, which I'll dive into in the next section. But for now, the TL:DR is, the pursuit of money leads to:

- Maintaining instead of alleviating deep-rooted insecurities.

- It keeps us on a never-ending treadmill to prove our worth but never tells us we can get off.

- It makes us see people and relationships as less valuable than status and stuff.

- It makes us feel, well, less free and more alone.

Money isn’t the friend you think it is 🤯

The work of political scientist Ronald Inglehart is useful in understanding this one. He spent much of his career looking at the broader cultural reasons why we become more or less materialistic.

The TL:DR of four decades' worth of work is: that we become more materialistic during times of economic and political uncertainty, and less when things are calmer. More specifically, Inglehart said, that when people experienced uncertainty and insecurity during childhood, i.e. their needs for security, safety, and sustenance were not consistently met, their drive towards materialism increased.

He found this consistent across countries, and even between generations. So parents who grew up during the recessions of the 1970s, and 80s, or family members who lived during war, will often be more motivated to acquire symbols of wealth and security over those who don’t.

The problem with that, said Inglehart, was pursuing materialistic things didn’t seem to alleviate that insecurity, it prolonged it. But because it’s how we’ve shaped our lives, it’s very difficult to change track so late in the game.

When do we feel worthy? 🤔

Here’s a question: do you feel, worthy? Well, do ya, punk? Sorry. I binge-watched a bunch of Clint Eastwood films last weekend.

But Dirty Harry aside, worthiness is a part of our worlds we don’t spend a lot of time thinking about. It’s like cress or Basingstoke. Sure, we know it’s there, but who cares? But In the context of money and materialism, understanding where we derive self-worth is important to understanding the money maze.

There is something called the Aspiration Index. It’s a series of questions designed to understand what are your primary drives and motivations in life. They are roughly broken into two categories: intrinsic - meaningful relationships, personal growth, community contributions - and extrinsic - wealth, fame, and social status. Feel free to take the test above if you’re interested.

What the Index has found, again and again in the 30-odd years it's been available, is that people who focus their aspirations on extrinsic values were less happy, had poorer mental health, and also poorer physical health. In essence, when our self-worth came from the outside, it was pretty crappy at making us feel better on the inside.

That’s because, for many thinkers, the pursuit of money and materialism often comes at the expense of other things. Robert E Lane, a political scientist describes chasing money as the equivalent of encouraging a “kind of famine of warm interpersonal relationships, easy to reach neighbors, or encircling, inclusive memberships and of solid family life.”

People as Objects ⚽

Next on the list is how the pursuit of money makes us see people differently. As we saw in the previous section, materialistic pursuits often crowd out pursuing more intrinsic ideas of self-worth.

The result of this is we see relationships and community as low priority; materialistic people are less invested in the people around them. Psychologist Shalom Schwartz, who has studied values across 40 countries across the world found something startling. When we prioritize values that focus on wealth, social recognition, preserving public image, and being successful, they come at the expense of, and in opposition to ideas around caring for others, and preserving the welfare of people and nature more broadly.

Take this a step further, and we see people as means to an end: other people are designed to facilitate our needs, instead of us living in harmony with there's. It’s why CEOs are very good at running companies: they find it easier to make decisions that can lead to harming others.

Philosopher Martin Buber called these I-It relationships, in which others’ qualities, their experience, feelings, and desires are often ignored, or only seen in terms of how they benefit oneself. Essentially people become objects in which they may be used in a transactional way.

This is in contrast to I-Thou relationships in which people are considered broadly equal to themselves in terms of their wants and needs.

Money = Isolation 😔

Many psychologists believe that people’s emotional states are largely a function of how far they are from who, what, or where they would ideally like to be. This can turn up anywhere: from our bodies, our personalities, our relationships, and of course, how much money we have.

With the pursuit of money, there is, sadly, always someone with more. If we’re using this external yardstick, it can be a cruel teacher, as it never tells us when is enough. This causes us to chase something that doesn’t really care whether we win or lose. That makes us feel shit.

While that’s happening, we’re also isolating ourselves from others. This may be due to a feeling of competition and selfishness that sets in with the acquisition of wealth or status. It may also be because, quite simply, we don’t need other people to survive the way we did when we were poorer.

Patricia Greenfield of UCLA and Dacher Keltner of Berkeley have both (independently) found this in their studies; as we grow wealthier, we value independence more and social connectedness less. As for the physical element, it’s quite straightforward: the wealthier we become, the more likely we are to erect boundaries between ourselves and others—for example, by living in a bigger house with a fence around it.

This, as we know by now, leads to loneliness, lack of trust, and fear. Just ask a therapist for the super-rich. Or watch Succession: they’re a mean, distrustful bunch.

So what’s to be done? 💡

Money by itself does not cause these things. Money has no feelings and doesn’t care about you or anything you believe in. It’s more about what money means to us.

Growing up in a scarce environment can lead us to crave the security that money can bring. But money doesn’t listen to you when you’re sad, or make you smile, or tuck you in at night. People do.

If you’re new to my newsletter, the grand narrative that (I hope) ripples throughout my work is that relationships are the single most precious resource we have. And if you don’t believe me, go and read the Harvard Grant Study.

This research has spent nearly a century proving, that time and time again, the single biggest predictor of a long, happy life, was the quality and depth of the relationships, not the things we could acquire or buy.

You can take that to the bank.

Things we learned this week 🤓

- 🛌 The purpose of dreams? They may be helpful in helping us connect with others, says research.

- 😱 Most popular songs tend always about insecure romantic attachment, says study.

- 📚 10 words for feelings you’ve never felt able to describe.

- 📱Are smartphones actually bad for us? Depends which expert you ask.

If you would be so kind 🙏

I am terrible at marketing. Literally terrible. But I’m trying to get better, and I need your help!

If you enjoy my witterings, please do share with someone or subscribe, it really helps.

I love you all. 💋