The psychology behind the Netflix show, Baby Reindeer 🧠

What’s that, two newsletters in a week? What can I say, I struggle to maintain healthy boundaries. But I just had to step into my writing shoes and explore some of the ideas behind the absolutely brilliant Baby Reindeer on Netflix.

If you’re not familiar with the show, this week’s newsletter has a few spoilers, so I recommend you skip this one. Or better yet, send it along to that front who has been badgering you to watch it instead. Eyeballs at the ready? LEGO.

Talking Stalking 👻

The show is based on a true story by actor and comedian Richard Gadd. He plays Donny Dunn, a struggling comedian working at a pub in Camden.

One day a sad-looking woman named Martha walks into this pub and seems a bit down. Taking pity on her, he offers her a free drink after she declares she has no money. Not long after that initial moment of kindness, she’s spending every day at the pub.

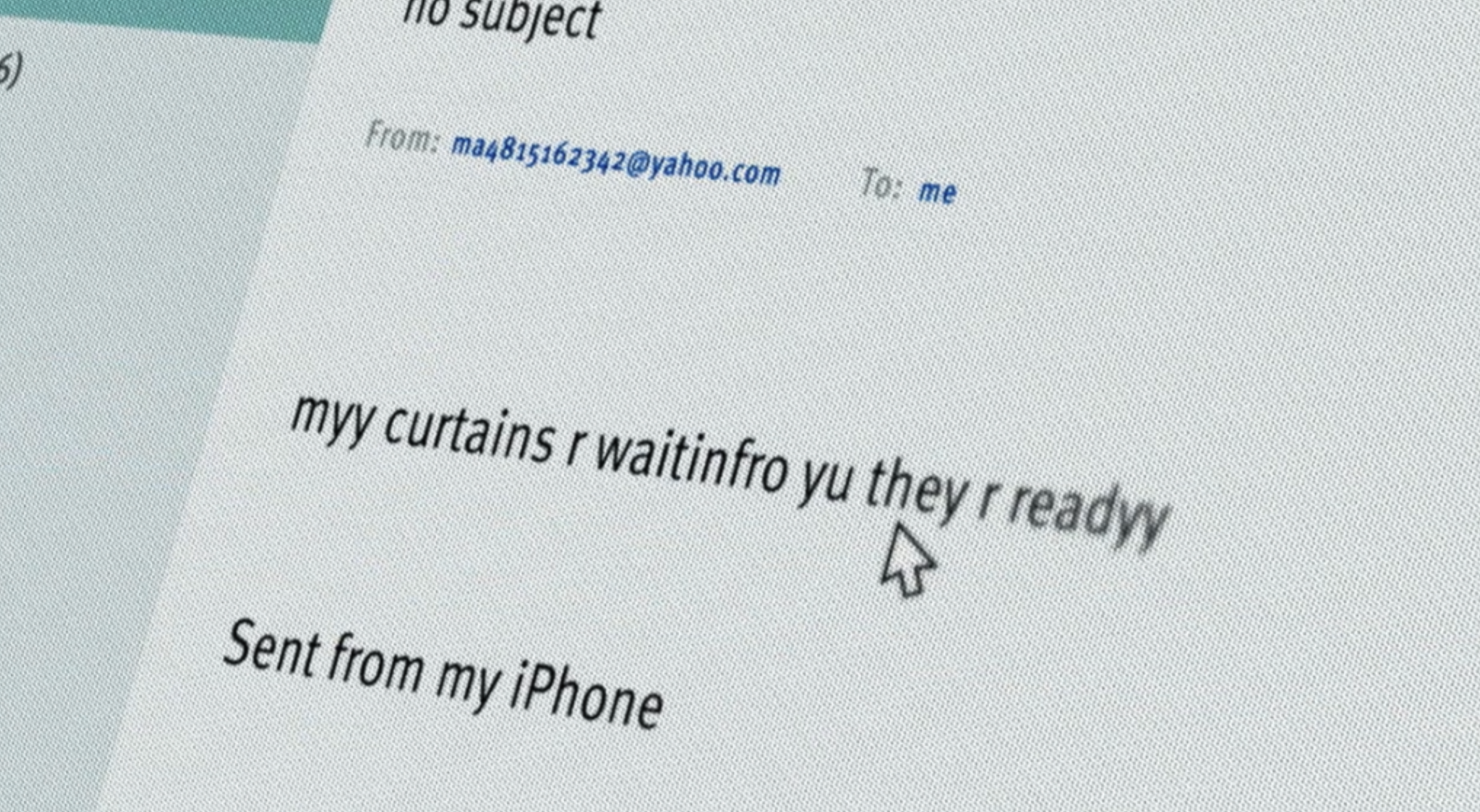

She creates weird and wonderful fantasies about her life as a high-flying lawyer - we learn later that there’s a grain of truth in her tales. She also acquired his email address and proceeded to send hundreds of emails per day, all signed off with the closing line “Sent from iPhone”.

Except, Martha doesn’t have an iPhone, it’s a noticeable quirk to the character’s inner world. She has identified this simple line as something valuable and uses it, over and over again. But the giveaway to what’s happening inside Martha comes out as her ability to type out the phrase each time dwindles.

Sometimes there are extra letters, sometimes there are very few, each time a reinterpretation of the simple sentence, but pushed a warped lens.

This distorted repetition is a key theme to this tragic story. Baby Reindeer sees a cast of characters all struggling to become something new. But in their quest for reinvention, find themselves being pulled back by the people they were before.

Before I get into that, I need to dust off my dusty psychology books and tell you a bit about repetition before we can explore what’s the relevance to the story.

Repeat After Me 🙊

Therapists have a mild obsession with repetition, especially when it comes to relationships. This all stems from Sigmund Freud’s initial observation that his clients tended to find themselves in the same relationships or acting out the same patterns of behaviour over and over again. He called it the Repetition Compulsion.

Where he found this idea most compelling was when his clients seemed to pursue or maintain experiences that they themselves have identified and understood to be problematic, but they continued anyway.

This flew in the face of Freud’s original assumption that we are all pleasure-seeking animals, only seeking the lovely things in life. Like ‘accidentally’ ordering twice the amount of pizza and not being charged for it.

Freud believed we did this because below the civil ‘conscious’ layer of ourselves, lie more primitive forces obsessed with fantasizing about our own demise. He called this a “death drive”.

Fast-forward to the modern day and our understanding of repetition has moved on a bit. What we know now is that repetition is about creating or maintaining situations that feel familiar and or comforting. These are typically based on painful and often traumatic experiences we’ve held onto.

When we have been neglected, abused, or hurt in some way, there is a part of us that holds on to it. Melanie Klein, another famous therapist, had a brilliant way of looking at it. The Viennese psychoanalyst believed that no one ever experiences what we would call “pure love”. That is, love that is constant, unconditional, and positive in our experience of it.

Instead, when we say love, what we really mean is that among those lovely caring moments are also less caring ones too. There might be ambivalence, frustration, rejection, and other bits that objectively seem bad. But because we have no frame of reference growing up, we readily internalise that special version of love (or attachment if you want to get psychological about it), and then repeat it with other people.

This is why you’ll have a friend who always seems to pick what you feel is the wrong partner. That partner may appear selfish and neglectful for you, but for that friend, that might spell L.O.V.E. if that’s what they experienced at a pivotal point in their life. If they believe love is at times nice and caring, but also destructive and terrible, that’s what they will tend to seek out.

Ok, so let’s go back to Baby Reindeer for a sec.

The Great Escape 🏃

While the first few episodes of Baby Reindeer focus on Donny’s relationship with Martha, the story broadens to include other examples of the vice-like grip Donny’s core beliefs have over him.

There’s the relationship with his girlfriend, his parents, and his mentor/abuser. I’ll try not to give away too many details of the story, but essentially what you watch is Donny’s desire for connection twinned with a belief he doesn’t deserve it. This heady combo pushes him into destructive relationships and pulls him out of those that might offer acceptance.

His parents appear initially stern and far away. Donny’s response is an infant-like smallness in which he doesn’t want to take up much space. But after he shares a painful experience with them, that steely exterior of mum and dad, especially dad, gives way to an opportunity to be accepted. But at the end of Donny's time with his parents, he has retreated back to the boy he once was. Closed off, unavailable.

Donny’s girlfriend, Teri, a therapist offers a safe, warm, loving environment for Donny. Initially, Donny responds well and enjoys this new type of relationship. As he begins to open up to Teri, he finds acceptance and love, but the price of that love and acceptance is that he must confront those parts of himself he doesn’t love so much. The result? Donny finds a way of alienating Teri to the point where she leaves him.

Of course, there’s Martha too. The bubbly stalker that oscillates between threatening and understanding doesn’t leave Donny alone. When he tells people about what is happening, including the police, their response is that he should leave. But he doesn’t. In some cases, he actually seeks her out.

Last, but not least, there’s Darrien, a comedy writer who takes a liking to Donny and sets about consuming him in graphic and distressing ways. This part of the story happens before when the series is set, and we see a younger Donny swept along by the flattery and attention he receives from Darrien. But then Darrien exploits Donny in a way that sends the character into a journey of self-loathing and alienation that never seems to resolve.

The story ends with Donny going back to Darrien, and re-immersing himself in the affectionate but abusive gaze of his abuser once again. For many friends and colleagues who have watched this story, a common theme emerged: why did Donny go back to Darrien, and why did he crave Martha, his stalker?

Baby Reindeer is a brilliant encapsulation of what happens when the templates we have for what love looks like - both for ourselves and from others - are distorted, or torn up, or shaky. Our desire to seek affirmation, affection, and attention can override every logical part of ourselves.

What the show tells us is painful. That despite the best will in the world, and people who care and support us, we often consistently choose things that we already know hurt us. Donny offers no happy ending. Instead, he shines a light on something as a therapist I see every day: the struggle to understand why we do the things we do, while also doing those very same things.

Things we learned this week 🤓

- 😔 Young people are now unhappier than the elderly.

- 🏃 Feeling lonely? Go outside, say researchers.

- 📉 A study suggests that being ‘woke’ makes you miserable.

- 🤖 Want to improve well-being at work? Say no to AI.

If you would be so kind 🙏

I am terrible at marketing. Literally terrible. But I’m trying to get better, and I need your help!

If you enjoy my witterings, please do share with someone or subscribe, it really helps.

I love you all. 💋