The psychology behind far-right radicalization 🧠

Earlier this month in the UK, something terrible happened.

In Southport, Merseyside, three children were killed and 10 others were injured as the result of the acts of a single individual.

Thanks to a whole bunch of false reporting, and amplification of that false reporting by prominent individuals, a series of hateful riots took place across the UK.

The people rioting have been described as many things: far-right, racist, anti-immigration, Islamaphobic, the list goes on. While many of you who read this weekly newsletter will not agree with any part of why they did what they did, I’m sure like me, you were curious as to why and how people become so captured by an idea or a sentiment that they start physically attacking others.

Why do people become radicalised by extreme ideas? Are some people more disposed to radicalisation than others? Is there anything we can do in our own lives to help anyone you know who might be on the fringes of some of the ideas shared on the streets earlier this month?

Well, that’s what I’m going to be exploring in this week’s Brink: the psychology behind radicalization.

Radical thoughts 🤯

Before I go on, it’s worth remembering that therapy and psychology have a habit of operating in a vacuum. That is, these disciplines tend to overlook social, cultural and political factors when trying to diagnose a problem. They try to look within the person, rather than around them.

This article will attempt to do both.

Over the last 20 years, there has been a lot of research into radicalisation. That research tends to group into three broad themes:

- What social, cultural, and political ideas amplify radicalisation

- What personality characteristics might make us more likely to be radicalised

- Underlying psychological ideas and issues that contribute to being susceptible to extreme ideology.

In this week’s newsletter I’ll cover some more than others, and of course, add in my own ideas on why we find ourselves in an increasingly polarised age, and what might we do to remedy it.

Focusing on the social and cultural, Psychologists Dr Tobias Rothmund Dr Eva Walther spent years interviewing experts on what wider ideas nudge people towards radicalisation. For Rothmund and Walther, it’s the growing economic inequality, the perception that resources have become more scarce, and an increasing sense that home is increasingly under threat from an increasingly mistrustful world.

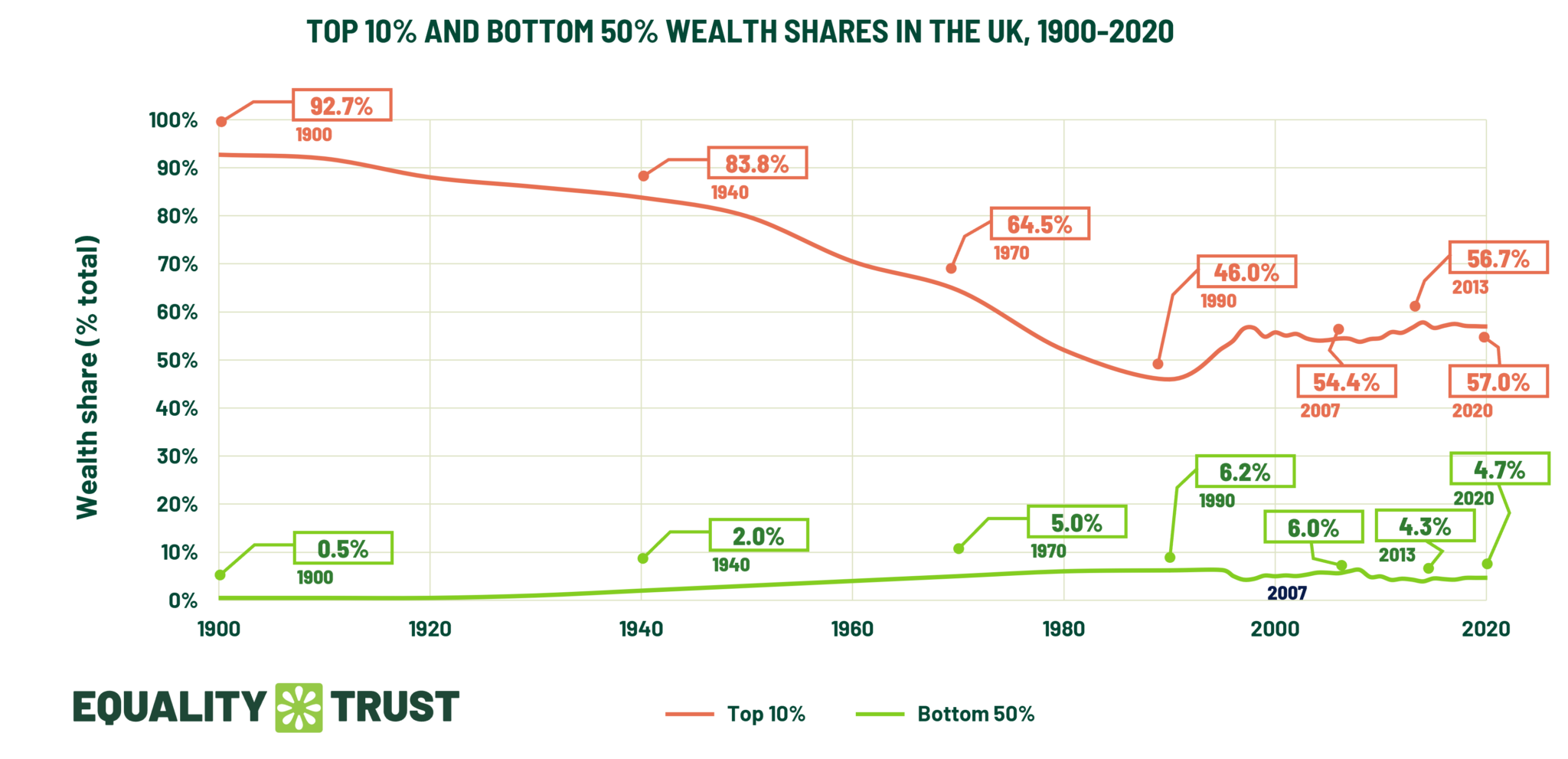

Over the last 30 years, the UK has become an increasingly unequal society. A case in point: the richest 50 families in the UK hold more wealth than half of the UK population, comprising 33.5 million people. If the wealth of the super rich continues to grow at the rate it has been, by 2035, the wealth of the richest 200 families will be larger than the whole UK GDP.

The below chart demonstrates this starkly.

"Right-wing extremist ideologies offer simple solutions to such experiences of loss and disadvantage," says Rothmund in their book on the subject.

This is shaped, says the authors, by the perception that "everything was better in the past" and that a return to traditional lifestyles would solve the ills of today. "Such interpretations relieve the individual by attributing responsibility to others, such as politicians or migrants, while at the same time strengthening their own self-efficacy. We can therefore speak of a kind of self-empowerment movement," Rothmund continues.

Poverty and inequality don’t cause extremism, but they make people more likely to feel hopeless and alienated from mainstream politics—fertile conditions for radicalisation. Researchers have documented this link in Pakistan, the Sahel, Nigeria and the United States.

Instead what we see in the UK, and elsewhere is that poverty and inequality need direction and energy to become fertile ground for radical ideas. That has been supplied, as many academics now come to realize through the shifting media landscape.

The current migration hysteria wasn’t spontaneous. In the early 1990s, fewer than 5 per cent of voters considered immigration an important issue. By 2010, it was one of the public’s most pressing concerns.

Between 2000 and 2006 the Sun, Daily Express and Daily Mail ran stories every day mentioning asylum seekers or immigration, generally portraying them in a negative light. The Conservative party adopted the “dangers” of immigration as a major talking point and the media increasingly gave a platform to anti-immigration “commentators” such as the former BNP leader Nick Griffin and Nigel Farage.

Since then, the right-wing press has flooded readers with headlines such as “True Toll of Mass Immigration on UK Life”, “The ‘Swarm’ On Our Streets” and “Foreign Workers Get 3 in 4 New Jobs”.

A cottage industry has also developed around legitimising and promoting conspiracy theories. Chief among these is the Great Replacement, which postulates that a cabal of “globalist” elites is plotting to replace white Europeans with Muslim immigrants.

The theory was referenced in the “manifestos” of terrorists Patrick Crusius (who murdered 23 people in El Paso, Texas in 2019), Brenton Tarrant (who killed 51 people in Christchurch, New Zealand, also in 2019) and Anders Breivik (the murderer of 77 people in Oslo and Utoya, Norway in 2011). And more recently, British political figures have been peddling it too.

I’ll come back to this idea later. But for now, I want to plant the seed that yes there may be certain types of people who may be more susceptible to these ideas, but that is supercharged when a media industry pumps out the same ideas.

Open to ideas 📱

Academics have more recently been exploring personality as a way of interpreting who is more susceptible to radicalisation than others.

A new study suggests that a particular mix of personality traits and types of unconscious cognition – the ways our brain takes in basic information – can be helpful for predicting whether someone is likely to take on extremist views: whether that be nationalism or religious fervour.

This study uses a broad brush, but what it suggests is that those of us who struggle with impulse control, find adapting to changes difficult, and overlook personal reflection in favour of external projection, increase - but does not guarantee - the chances someone might latch on to extreme ideas.

Digging deeper, the study argues that extremism is underpinned by a fixed worldview and a resistance to new evidence. In other words, once these views have been adopted, they become very hard to shift.

They offer the holder a way of satisfying basic needs: a need for order, structure, and avoidance of uncertainty or ambiguity. These views provide people with a defense against a world often bereft of order and certainty.

That manifests as an increased desire for obedience to authority, order, purity, and the familiar. These groups prefer to maintain a position of dominance - even though they often feel they are being oppressed.

Their belief in traditional values is often expressed through a lens that believes in subjugating women, disadvantaged and minority groups and of course, anti-immigrant and xenophobic stances.

But combing through the literature, there can be a sense of these people being distanced from the places and communities we live in. The UK riots of this summer were widespread. As was the violence. While racism is sadly, part of all societies, violence, thankfully is few and far between.

Why did these groups become violent? Professor John Drury, a social psychologist specialising in collective behaviour has some thoughtful insight.

“When part of a crowd, people may well see others as part of their group and feel a greater sense of belonging. The more people that share the same group identity, the more cohesion there is. Then in turn, the more support people will feel for enacting the group's identity."

The mindset of those enacting violence was that they had been lied to by authorities, and thus was the last line of defense against an imagined enemy, in this sense the police and asylum seekers.

In the days leading up to the riots in Southport, there was a large demonstration in London of a group representing the broad ideas of the far-right. Professor Drury believes this helped those who would subsequently take to the streets believe they were part of a bigger group in society who felt the way they did.

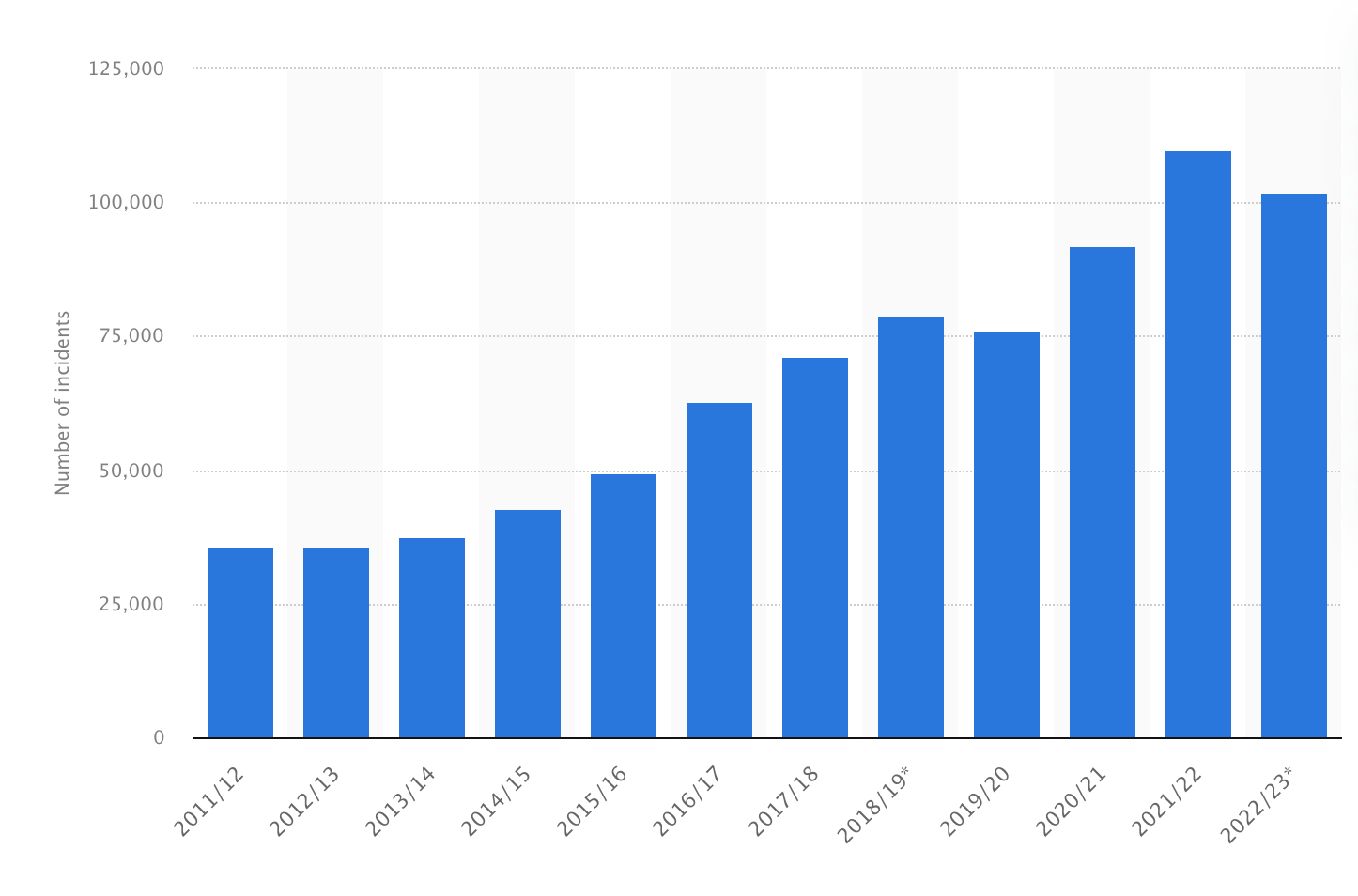

Indeed, the number of police-recorded racial hate crimes in England and Wales shows a worrying trend: that race-motivated violence has been steadily trickling up.

Zooming out further, this violence has been legitimised by the rise of far-right media groups and individuals, aided by the ambivalent stance of social media companies when it comes to policing racist content on their networks.

In essence, for the people enacting the violence earlier this month, what they saw on the TV they watched and the circles they moved in online is a world that mirrored how they feel. They felt like everyone felt the same way.

When they were in the streets and saw people acting violently, it helped legitimise their own feelings of anger and resentment. It showed there was a valid way to express them: by being horrible to other people, including the police.

But inside this belief lay the seeds for how to combat it.

Not one of us 🙅

After the horrible scenes of the beginning of August came something altogether more hopeful: thousands marched in opposition to the violence and racism they saw.

Culprits were arrested, sentenced, and jailed in record time. Social media was no longer the haven for racism and preaching violence - as several who spread hate online have been imprisoned for doing so.

What these people saw very quickly was the world they had been living in: one where violence, racism, and xenophobia seemed normal, was not in fact the world they lived in more broadly.

Pictures emerged of thousands of anti-violence protestors outnumbering rioters. Those who propagated the hate and violence saw they were outnumbered 100 to 1. This is how you stamp out racism: by showing that this is not the world we live in. Professor Drury in conversation with the British Psychological Society summarises this brilliantly:

- “Potential participants need to understand that there is not the wider public support they think there is for their views, that the opposite is the case.

- Prevent them mobilising and marching, to limit that capacity-building.

- Prevent their actions (including smaller acts of hate) from having a tangible impact – prevent them from turning their subjective identity into objective reality – by negating and canceling out their effects.

- Finally, as it is particular identities that are empowered or disempowered, assert and support collective identities antagonistic to theirs. For example, well-organized and attended groups and activities based on international class solidarity help to defeat racism and xenophobia on the streets. This makes solidarity a more realistic aim than any xenophobic or racist vision."

These points don’t sit with a government or a lobby group but with all of us. Sure, some of us, like politicians and social media executives do have an oversized role in shaping this debate. And they should be doing more, much more.

But away from the political sphere and into the personal, if we want to live in a world where the horrible events of July and August 2024 no longer happen, we need to remind those around us that these radical views do not align with the views of the many.

Hate dies in a vacuum. The fewer places and spaces there are for these ideas, the less space they have to flourish. We all have a role to play in that.

Things we learned this week 🤓

- 🎨 Being creative can make you happier and live healthier for longer.

- 😡 5 second breaks can help lower the time we argue.

- 👶 Want to give your baby a better start in life? Hold them more.

- 😔 Loneliness turns up in our dreams says study.

Just a list of proper mental health services I always recommend 💡

Here is a list of excellent mental health services that are vetted and regulated that I share with the therapists I teach:

- 👨👨👦👦 Peer Support Groups - good relationships are one of the quickest ways to improve wellbeing. Rethink Mental Illness has a database of peer support groups across the UK.

- 📝 Samaritans Directory - the Samaritans, so often overlooked for the work they do, has a directory of organisations that specialise in different forms of distress. From abuse to sexual identity, this is a great place to start if you’re looking for specific forms of help.

- 💓 Hubofhope - A brilliant resource. Simply put in your postcode and it lists all the mental health services in your local area.

I love you all. 💋