The myth of the mid-life crisis 🧞

According to my newsletter analytics, many of you lovely, caring, thoughtful readers are in or around the midpoint of life. That is, you’re probably somewhere between the ages of 40-60. I know I certainly am.

As a result, you are a prime candidate for a mid-life crisis: that existential turning point where we are no longer young but not quite old, we’re just somewhere in the middle. Which inevitably means we’re one step away from falling into the giant bear trap of mid-life cliches.

If you’ve indulged in an overpriced luxury item, given yourself a makeover, ended a long relationship or even blown up your entire life in the pursuit of something new, society will scratch its chin, nod understandably and say, dear reader, you are having a mid-life crisis. But is this gentle implosion a foregone conclusion?

Is it inevitable we have these crises, or is there an alternative where those middle decades don’t carry the same sense of dread and uncertainty as once thought? Well, in today’s Brink, that’s exactly what I want to find out.

Mid-life: A brief history 🤔

So the term mid-life was first written about by Canadian-born psychoanalyst Elliott Jacques in 1965. He described it as:

“The compulsive attempts, in many men and women reaching middle age, to remain young, the hypochondriacal concern over health and appearance, the emergence of sexual promiscuity in order to prove youth and potency, the hollowness and lack of genuine enjoyment of life, and the frequency of religious concern, are familiar patterns. They are attempts at a race against time.”

Heady stuff. But interest in what was then called the “dangerous age” by psychologist Granville Stanley Hall had begun much earlier, in the 1920s.

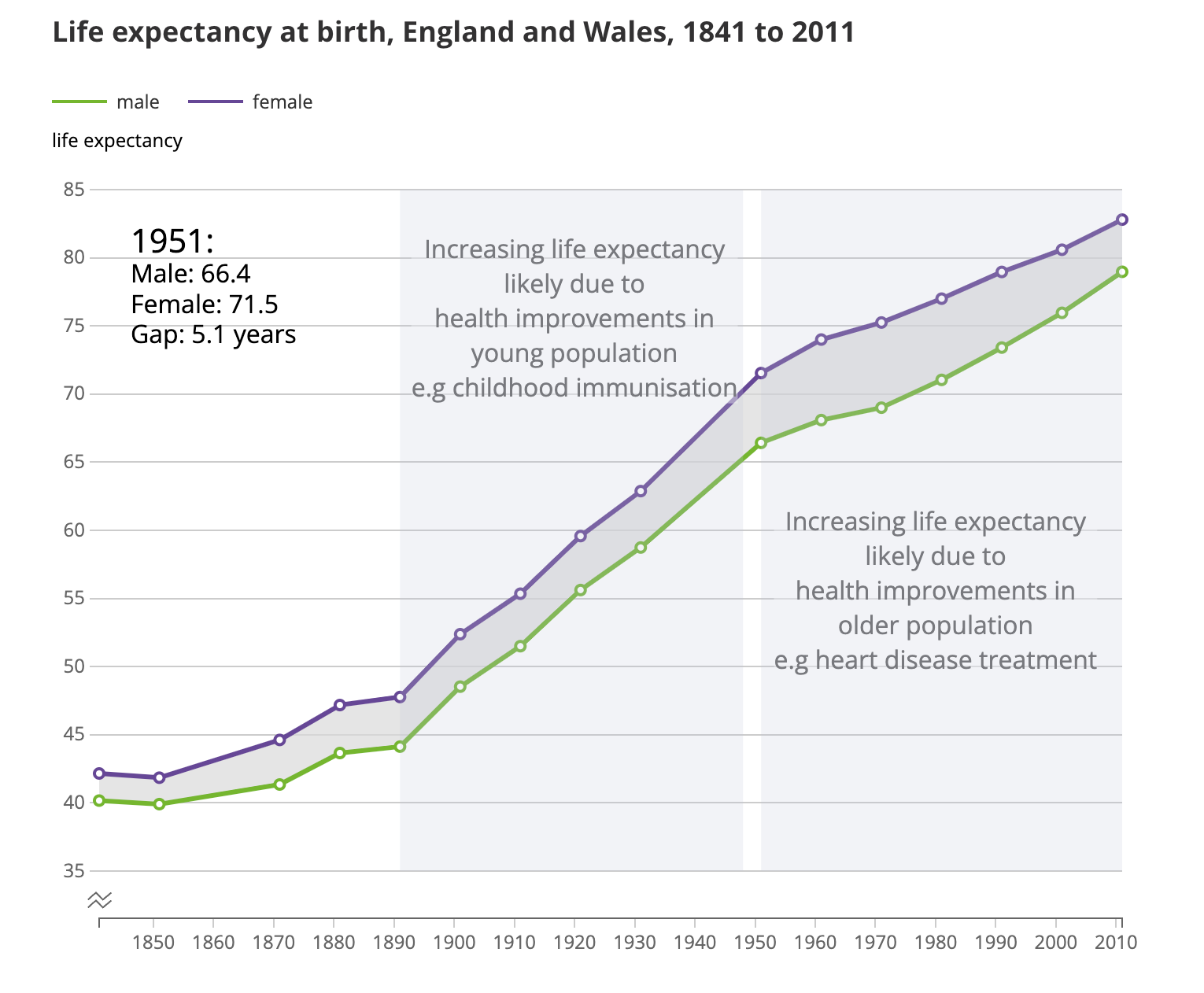

That’s because, for the first time, people were living a lot longer than they were in the 1800s. In 1840, life expectancy was 40 for men and 42 to women. By 1950, it was over 60 for men and over 70 for women - meaning there was a big chunk of life that hadn’t really been present before. As a result, a new phenomenon appeared.

For Jacques and others, this phenomenon tended to turn up in men (and sometimes women) who hadn’t quite achieved what they thought they should have.

In fact, said Jacques, those who reached mid-life without having achieved what was culturally seen as successful: marriage, children, a level of professional achievement - they (meaning men) were likely to start displaying what Jacques believed were the hallmarks of the midlife crisis:

- disillusionment with life

- dissatisfaction with work

- a desperation to postpone mental and physical decline

- detachment from family responsibilities

- infidelity with a younger, more athletic accomplice

While Jacques was keen to point out it was more often than not society’s expectation on people to achieve a certain level of status (more on that later), many thinkers saw our biology as the reason for the sudden sense of unease.

It was believed that hitting midlife meant we became aware of our imminent physical decline. We were no longer the fighting fit whipper snappers of our 20s and 30s, and all we can see in front of our sagging faces is death on the horizon. While that might sound macabre, that very much is the flavour of how they wrote back then.

It’s important to note that there was little emphasis on what happened to women during these periods (surprise!). But the general consensus was that some women did experience this phenomenon.

Their ticking biological clocks (fun fact: the term biological clock was first coined by American journalist Richard Cohen in 1978) were accelerating, which, according to the theory, meant they were no longer of any value to society because they weren’t producing children (not my words I promise!) which caused an alternate version of the mid-life crisis.

The consensus seemed to be then, that our failing bodies were to blame for the midlife crisis. Some men even went so far as to blame the menopause as the reason they were having a tough time. Tsk.

Thankfully, the biological approach fell out of fashion. It was Jacques’ idea about society and culture that became the dominant way to explain why those in their forties and above started freaking out. It also gives us some clues today as to how to navigate around it.

Culture Club 🕺

During the 1960s, when Jacques and his mates were telling us we were all in a crisis, a theory emerged that helped put these ideas into perspective. The Life Course approach, or Life Course Theory, was an idea developed by American sociologist Glen Elder.

Elder reckoned that life was essentially, "a sequence of socially defined events and roles that the individual enacts over time." By that he meant, there were a number of milestones, roughly tied to how old you were, that you were likely to have gone through as part of a society’s expectation of you.

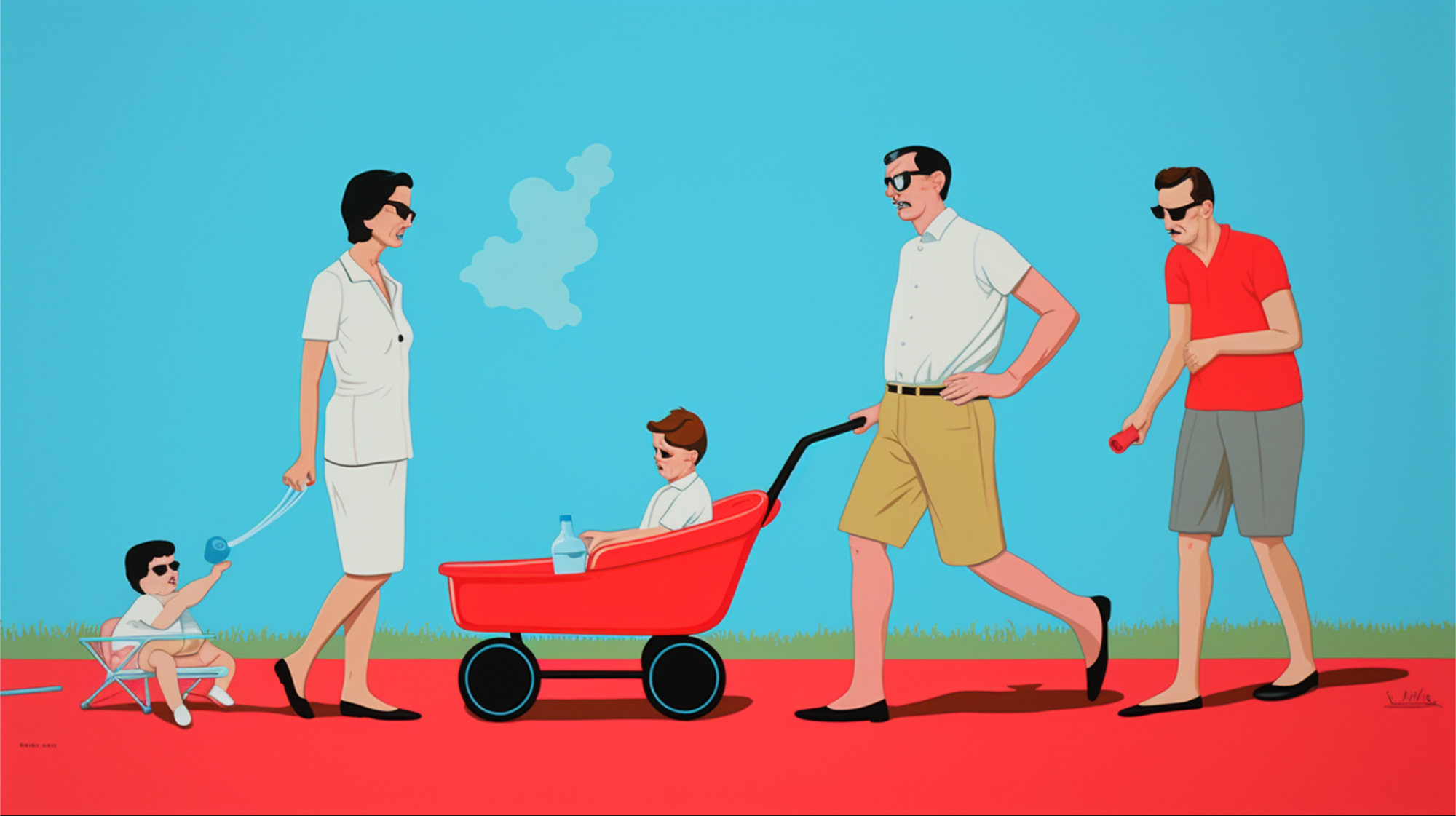

A case in point: in the 1950s and 60s, men typically left home between the ages of 16-18, they were married by around 24-25, had children by the time they were 30 and then would work for a fixed number of years until retirement.

For women, meanwhile, their life course tracked differently. Women would marry earlier, around 20 or 21, and they could have children in a relatively tight cluster of years. They would tend to leave the workforce when they had children and spend most of their lives in the service of their partners and family.

Now this narrative, while simplified in lots of ways, became a sort of yardstick by which people could view themselves in contrast to the rest of society. If you were on track, happy days. If you weren’t, something had gone terribly wrong. This idea was first noted in the comic strip Keeping up with the Joneses, which first appeared in 1913.

The cartoon, created by Arthur R. Momand depicted the life of the McGinis family, who were locked in an eternal struggle to keep up with the Joneses, the mythical neighbours who always seemed to do better. Weird to think that more than a hundred years ago, people were uneasy about how well they were doing when comparing themselves to others. Sound familiar? Anyway. Let’s go back to the life course idea again.

With most people following this roadmap of living, by the time many of them reached the dreaded middle age, their children, now teenagers, were also going through their own troubled age. So were the parents of the couple in focus. Thanks to longer life, people in their 40s and 50s, had parents in their 70s and 80s.

This meant that our couple was sandwiched between their parents who required more care, and their teenagers who, well, despised them. This led many to believe the midlife crisis was the result of people being squeezed between two other generations who suddenly demanded different things from them.

This was compounded by the relatively new idea that couples, who could live for more than 50 years after the birth of their last child, were expected to remain fulfilled for the majority of their lives. Enter the mid-life crisis: the response to all the things I have laid out above. It all seems very logical, doesn’t it? Life tends to get terrible at this midpoint, and everyone else is to blame.

But as you’ve read this section, you’ve probably started to notice something: the Life Course idea that we move through fairly fixed points doesn’t really seem all that relevant anymore. Fewer people are getting married, having children, and having jobs that would last 30 or 40 years are largely a thing of the past.

While this might sound like doom and gloom, this societal shift has actually liberated the vast majority of us from the idea that 40-60 is terrible.

Tearing up the rule book 📚

The idea of the mid-life crisis was designed to capture a very twentieth-century problem: we all follow a typical path through life, and when we reach the middle of life, we are being battered from all sides: our parents, our children, and our declining physical prowess. But the 21st century is different.

The Life-course model doesn’t really fit anymore. We are more able to shape and define what sort of life we want more than ever. More young people run their own companies, older people are more likely to get married than young people, science has helped push childbearing years back later in life, and many more people are choosing to redefine retirement. Just ask this year’s Presidential hopefuls - Biden is 81 and Trump is 77.

Research also shows that the mid-life crisis has in fact, become a surprisingly rare phenomenon. Only 1 in 10 of us seem to experience what could be defined as a mid-life crisis.

The doom and gloom of our 40s and 50 was a revolt against what life expected from us. So what does life expect from us now?

We all age, but we experience age differently. While that idea might seem biological, I want to argue it is also psychological and societal. Some of us may adhere rigidly to the life course idea, ensuring we keep up with 2024’s version of the Joneses, whoever they are (the Kardashians, perhaps?) Others tear that rule book up early and keep doing so throughout life, intuitively responding to what they believe is right at the time.

The key to whether we experience a crisis in middle age I believe is really down to what we feel we are supposed to have achieved by this point, and what our potential is to achieve more later. If we feel we’ve reached the pinnacle of our lives now, the rest of it may very well look a bit bleak. But what if the best of you is yet to come?

Age isn’t purely a biological fact. It is, like pretty much everything we experience, a construct that we experience. The midlife crisis is a myth: it is up to us to decide if we believe that is true or not.

Things we learned this week 🤓

- 🧬 ADHD might be a quirk of evolution, say researchers.

- 🤑 Entrepreneur? How good looking you are has impact on your ability to raise capital.

- 🧑🔬Want to learn something new? Find a teacher you like, first.

- 💑Love languages: they are not a thing.

If you would be so kind 🙏

I am terrible at marketing. Literally terrible. But I’m trying to get better, and I need your help!

If you enjoy my witterings, please do share with someone or subscribe, it really helps.

I love you all. 💋