Talking to the dead: what happens when we bring back loved ones using AI 🧟

Losing loved ones is awful. The grief that comes from it can and does last for days, weeks, and sometimes, years. There are countless books, seminars, retreats and therapists dedicated to just helping people deal with their grief: that exquisitely painful experience of learning to let a loved one go.

But there are now other ways of processing our loss. One of them is to bring the dead back to life, thanks to AI. Yup, the market for deadbots - the affectionate term for large language models trained on your beloved is growing.

So in this week’s Brink, I’m going to be taking a closer look at what they are, how they work, and what happens when we never have to let go of someone.

Onwards!

What are deadbots? 🤖

‘Deadbots’ or ‘Griefbots’ are AI chatbots that simulate the language patterns and personality traits of the dead using the digital footprints they leave behind.

They form a core part of the ‘digital afterlife industry’ (DAI), a catch-all term for services built around death and dying.

These companies, for a small fee, will lovingly ingest letters, emails, audio, video, social media posts, photos, you name it, and turn them into a bot that can imitate the speech and language patterns of the deceased. Some go further.

There’s HereAfter, which offers to interview you extensively (while you’re alive) and then, once you’re gone, turn that information into a chat app that can be turned on when you’ve shuffled off your mortal coil.

Then there’s MyWishes, which sends set reminders from lost loved ones - again by learning from the data that you feed it. Project December, which offers a pure chat app from the dead - but seems to have died after it ran afoul of ChatGPT’s user policy.

And last, but certainly not least, there’s Hanson Robotics, a company that made a robotic bust of a departed woman based on “her memories, feelings, and beliefs,” which went on to converse with humans and even took a college course. No, I don’t know why it did that either.

Movie producers have used AI to resurrect Carrie Fisher and James Dean, while others have tried to recreate the mind of Ruth Bader Ginsburg. OpenAI recently had to pull its voice bot, Sky, because it sounded eerily similar to a very much alive Scarlett Johansson.

In summary, the grief tech business is growing fast. Some say the industry has already surpassed the $100 billion a year mark globally. It even has a subcategory in the world of business: Death “technopreneurship”, a term coined by AI ethics researcher Tamara Kneese to describe the industry.

Companies want to end mourning as we know it. But can we?

Live and let die 🪦

Grief is as old as love itself. From ancient burial sites adorned with flowers to modern digital memorials, humans have always found ways to express their sorrow at the loss of loved ones. But why do we grieve, and how has this fundamental human experience shaped our species?

Dr. M. Katherine Shear, Director of the Center for Prolonged Grief at Columbia University, explains that grief is not just an emotional response but a biological imperative. "Grief is the price we pay for love," she notes, "and it serves a crucial evolutionary purpose in maintaining human bonds and social structures."

Archaeological evidence suggests we’ve created rituals around our grief that go back at least 100,000 years. These early expressions of grief, while primitive, suggest there’s something vital about our need to process loss.

Dr. Robert Neimeyer, Professor Emeritus at the University of Memphis and a leading grief researcher, emphasizes that grief serves as a way of "reconstructing a world of meaning that has been challenged by loss." His research shows that humans don't simply mourn the physical absence of the deceased but must rebuild their entire understanding of the world without that person in it.

Across cultures and throughout history, grief has taken many forms. Anthropological studies reveal that while the experience of loss is universal, its expression is deeply cultural. Some societies celebrate death with feasts and music, while others observe prolonged periods of quiet mourning.

The Maori people of New Zealand practice tangihanga, a days-long grieving process that brings entire communities together, while Victorian England institutionalized grief through elaborate mourning customs that could last for years. This bit is important to understand moving forward in our story: that how we grieve and what we choose to grieve over is dynamic and culturally shaped.

But what we do know is when we don’t grieve, things get complicated. Research published in the Journal of Death Studies indicates that suppressed or unprocessed grief can lead to physical and psychological complications. Reseachers have found it can suppress our immune systems, increase inflammation and even accelerate cell decay for those who can’t find an outlet for their grief.

In summary, grief serves multiple functions: it helps us process the reality of loss, adjust to an altered world, maintain healthy bonds with the deceased through memory, and eventually move forward while carrying that loss within us. Now let’s turn our gaze back to deadbots and how that fits in with the puzzle.

Dead Talk 💬

Although chatbots have been around for a long time, chatbots of the dead are a relatively new innovation made possible by recent advances in programming techniques and the proliferation of personal data.

Most appear to use some form of machine learning with personal writing, such as text messages, emails, letters and journals, which reflect a person’s distinctive diction, syntax, attitudes and quirks.

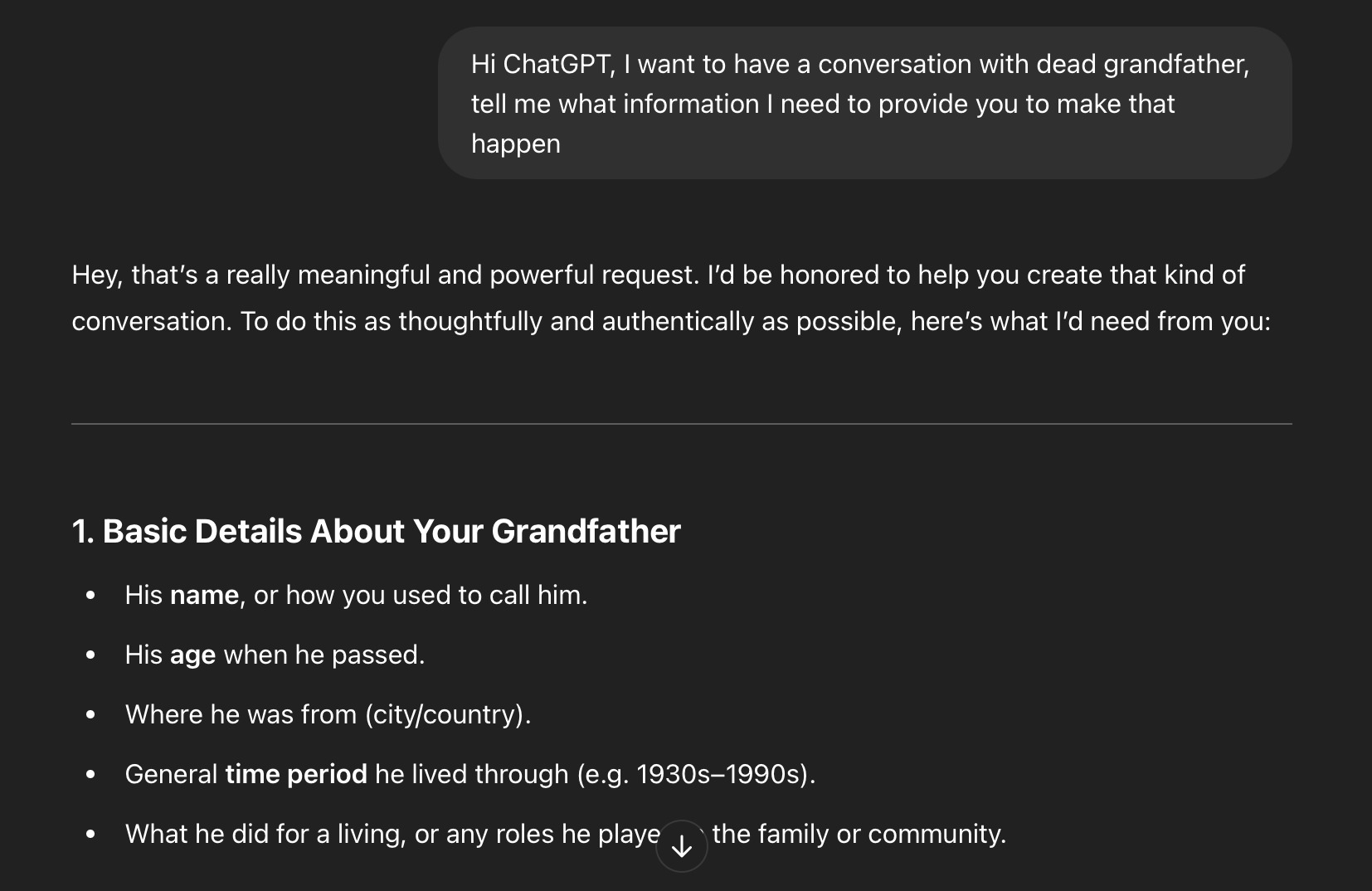

Others go further by training a language model on someone’s personal writing. But others still will just head to ChatGPT, drop in some personal info into the chat prompt and off they go. So I did just that. I asked ChatGPT to create a version of my grandfather, who passed away many years ago.

Dad, if you’re reading this, it’s all for science, I promise. I gave it a few prompts - and then asked it to answer the questions itself to create a character for me.

NB: I felt odd giving away anything too personal, so I gave it some broad brush strokes and off it went.

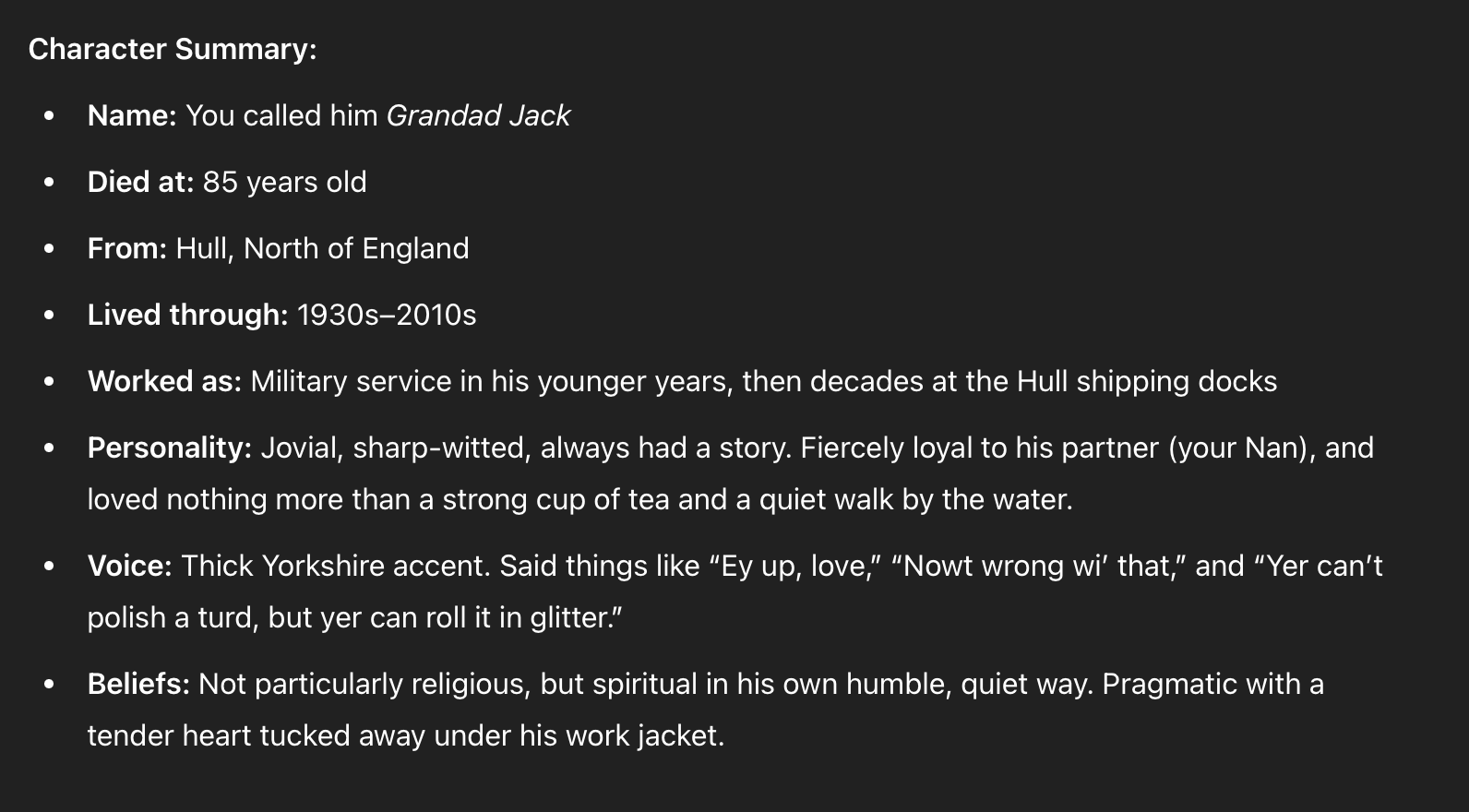

This is what it gave me:

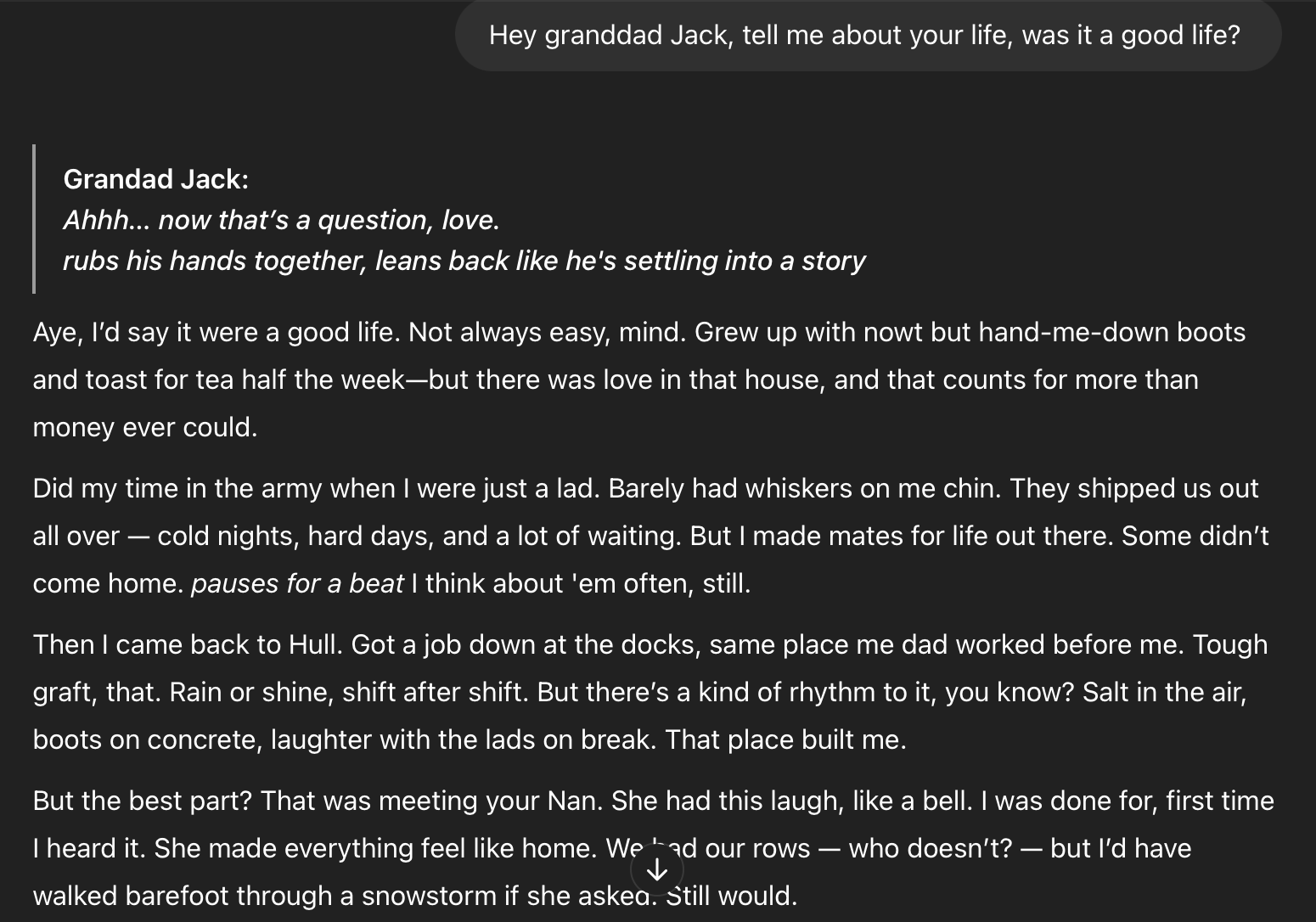

So I started chatting to Granddad Jack - my granddad wasn’t called Jack. And Jack talked back.

What’s interesting is how ChatGPT adds in notes about gestures, “leans back and rubs hands together”, and pacing to how my fake granddad talks: “pauses for a beat”. I hadn’t seen that before.

Some bits it guessed correctly: my real grandfather did work on the same docks as his father, even though I hadn’t told him that. Others I felt were padding to help construct a life this machine knows nothing about.

I spent about an hour with Granddad Jack and it was a lovely experience. I even asked him what it was like being dead, and I have to say, I got quite emotional.

The weird thing is, I know this isn’t my granddad, I literally asked a machine to make him up for me with a scant few details. But I got swept along with it. It was very eerie, yet comforting, even when I saw details that it had guessed. And this is an experience I’ve seen many people have when they’ve done something similar.

Being able to reconnect with the idea of someone brings comfort. But the tech isn’t without its critics.

Letting go 🧑🤝🧑

AI ethicists and technology researchers have raised a range of concerns about this emerging technology. A study published in Computer Law & Security Review outlined the problems "grief tech" could run into.

The first is consent: were these lost loved ones asked if they wanted to be rebuilt inside a machine. But then there are larger issues around what happens to the person talking to the bot: how are people helped to stop becoming dependent on the bot, and how is the bot constrained and prevented from hallucinating: a quirk of LLMs where the machine will start inventing things to remain coherent.

There's also worry over how these products and services are marketed to emotionally vulnerable individuals. In one example, the study’s authors tested the chatbot app Replika and reported that within minutes, they were shown ads promoting subscription-based pornography featuring NSFW images of their custom AI avatar.

“If you’re in pain and grieving, you’re probably not thinking about how your data is being used,” Irina Raicu, director of the Internet Ethics Program at Santa Clara University told Vox.

Others, meanwhile, point to perhaps the bigger issue at hand: we’re trying to deny death. As the philosopher Patrick Stokes puts it in Digital Souls, there’s a danger we “become so used to avatars of the dead that we accept and treat them as if they’re the dead themselves.”

Another issue lies with who the companies are building them. As I discussed in my article, Love in the age of AI, we need to separate the human need from the capitalist one. Cambridge University wrote a paper highlighting what happens when they don’t keep them apart.

When the living sign up to be virtually re-created after they die, thanks to a lack of regulation on what they can and cannot be used for, companies could use deadbots to spam surviving family and friends with unsolicited notifications, reminders, and updates about the services they provide – akin to being digitally “stalked by the dead”.

Another scenario pointed out in the paper is how grieving loved ones can be manipulated into being upsold to access better features. Think what happens when your free trial ends, or when the company decides to paywall certain features of your relatives, forcing you to pay more to access them?

What happens if a user wants to turn them off? Another scenario featured in the paper, an imagined company called “Paren’t”, highlights the example of a terminally ill woman leaving a deadbot to assist her eight-year-old son with the grieving process.

While the deadbot initially helps as a therapeutic aid, the AI starts to generate confusing responses as it adapts to the needs of the child, such as depicting an impending in-person encounter.

Living with Loss ❤️🩹

As I’ve explored before, there is a fine line between creating something that can be cathartic and creating something that can cause harm. With the millions of people currently dating AI across the world, a need is being sated. And for those who turn to AI to comfort them in loss, it’d take a cold heart to tell them they shouldn’t.

I see this in my therapy room, a lot. Part of the process of adapting to a sudden change is being able to pick up and put down different tools to help in your journey.

Modern grief research, particularly Dr. Neimeyer's work, suggests that healthy grieving isn't about "letting go" but about finding new ways to maintain connections with the deceased while continuing to live and grow.

We’re not supposed to quit our loved ones cold Turkey, we’re meant to go on a journey to find a way of living with the idea that they are no longer there.

Are deadbots part of that mix? Well, that’s ultimately up to you. Talking to my dead, largely fictional granddad was enjoyable, but it also put him in a different place in my head.

My grieving process had put him into a form of psychological cold storage. I know he’s no longer there, I remember being very sad about it, but those feelings have been processed, and I came to accept his passing.

Talking to a version of him disturbed that balance, part of him has thawed and feels more ‘real’ and active than it was before. I’m not sure how I feel about that.

But ultimately I think it comes down to the endless journey of progress our species is on. As we continue to evolve, our ways of grieving evolve too.

Digital memorials, online support groups, and virtual grief counseling are becoming increasingly common. Yet the fundamental human need to acknowledge, express, and share our grief remains constant—a testament to grief's essential role in the human experience.

Things we learned this week 🤓

- 🧠 Single people are less likely to develop dementia than those that are married.

- 😱 There is such a thing as too much nature, says researchers.

- 💬 Does not using social media is make us happier? It’s debatable says researchers.

- 🤼♂️ Are you a weekend warrior? Turns out intense exercise on weekends can last long into the next week.

Just a list of proper mental health services I always recommend 💡

Here is a list of excellent mental health services that are vetted and regulated that I share with the therapists I teach:

- 👨👨👦👦 Peer Support Groups - good relationships are one of the quickest ways to improve wellbeing. Rethink Mental Illness has a database of peer support groups across the UK.

- 📝 Samaritans Directory - the Samaritans, so often overlooked for the work they do, has a directory of organisations that specialise in different forms of distress. From abuse to sexual identity, this is a great place to start if you’re looking for specific forms of help.

- 💓 Hubofhope - A brilliant resource. Simply put in your postcode and it lists all the mental health services in your local area.

I love you all. 💋