Mental Health has an influencer problem 🤑

May is Mental Health Month. The initiative, first started in 1949 by the National Association for Mental Health in the US was designed to help raise awareness of all things the mind.

While historically it has been governments that have been the key advocates of better emotional and psychological awareness, a new group has entered the chat: influencers.

While the vast majority of posts on social media can and do help people understand they are not alone in struggling, there’s a growing concern that influencers are exploiting people’s suffering for financial gain.

In this week’s Brink, I’m going to be exploring the idea that our mental health is being used against us.

Influence’za 💸

Influencers and mental health have become big business. The biggest have millions of followers and earn millions of dollars through their short, simple messages about mental health. Oh, and their merchandise, books, experiences, events and donations to their pages.

Do you have TikToker Sienna Gomez’s “did you eat today?” sweatshirts? What about Instagram influencer Corinna Kopf’s anxiety apparel? Maybe YouTuber Demetrius Harmon’s “You Matter” hoodies (which were initially advertised with a 40 percent discount for fans who had self-harmed).

Influencers push promo codes for online therapy sites like BetterHelp. Fine you might think. Helpful, even. But should they earn a reported $200 per sign-up? Especially when the company has repeatedly found itself in hot water over the efficacy of its services?

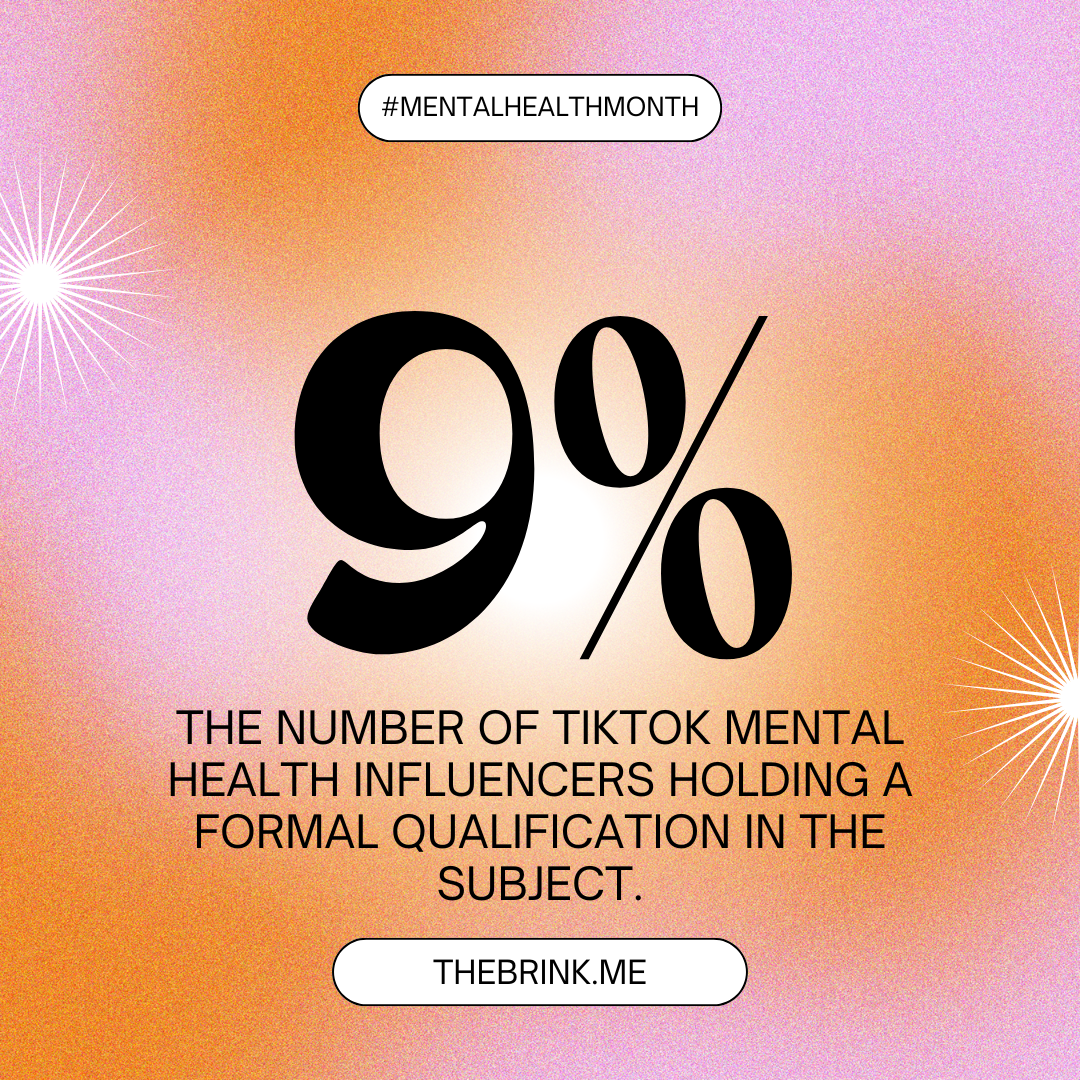

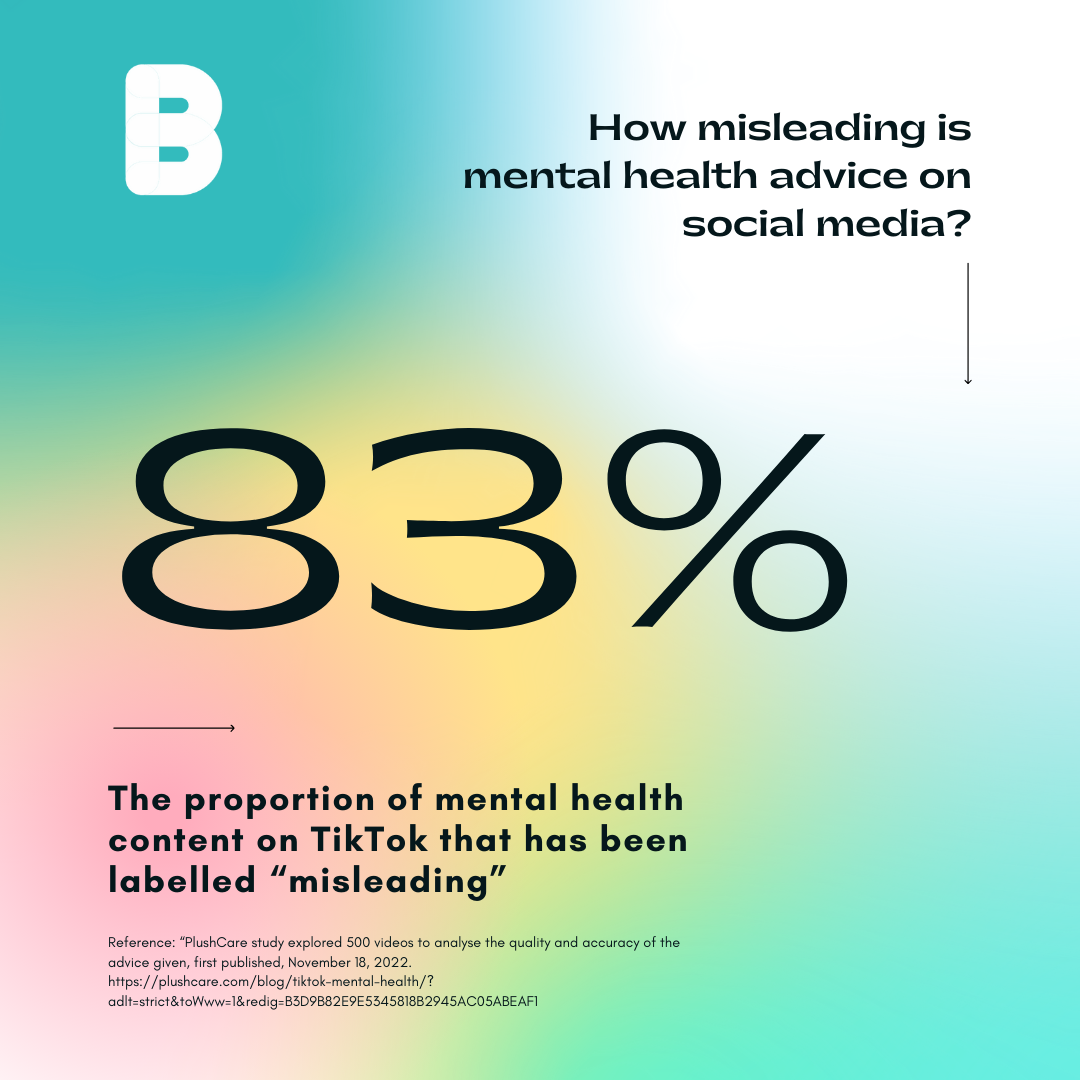

Mental health makes influencers money. But they often do so without much consideration for what they might be telling you to do. In a recent study of TikTok influencers peddling mental health, 83.7% of mental health advice on TikTok is misleading, while 14.2% of videos include content that could be potentially damaging.

The reason? The vast majority do not have a formal qualification in the discipline they claim to be an expert. In the same study, just 9% of influencers possessed formal qualifications, meaning they weren’t regulated by any governing body. The networks themselves do little to regulate the space too.

A case in point: when the NHS has to publicly call out Instagram for not doing enough to curb content that exacerbates body dysmorphia there are few levers in place to stem the tide of bad content.

The result is a sea of, well, shite. More data supports this:

- 100% of the content for ADHD contained misleading information, the most of any condition in our analysis.

- Content covering bipolar disorder (94.1% of videos) and depression (90.3% of videos) were also found to be highly misleading.

A whole generation of young people are being guided by unregulated, unqualified experts. But why?

The Dunning-Kruger Effect 🔬

Most of the time, humans will over and underestimate their knowledge or abilities. When we overestimate how good we are, or how much we know about a certain subject, it’s called the Dunning-Kruger effect.

While this is completely normal and all of us have some version of this in certain areas, the internet and the loving algorithms that manage it, care little for cognitive bias.

Likes, clicks, and engagement are what drive content. When you have a generation of young people struggling more with mental health than any other, content that speaks about their struggles is popular. As a result, content that feels authentic and real gets prioritized over content that might be more accurate but doesn’t carry the same emotional heft.

Influencers share intimate moments – like filming panic attacks or posting tearful selfies – so their recommendations seem reliable and heartfelt when they eventually arrive. By being vulnerable, they get views. By encouraging comments, their profiles get engagement. Companies pay them for access.

Regular pathways to emotional support do not - because they can't use the same para-social techniques to grow followings, because thankfully, most are regulated. The result is people turn less to medical services and more to the services of the people they follow.

In England, millions of people with poor mental health are no longer seeking NHS help. A chasm has opened. While demand is surging – the rates of people using drugs to combat anxiety, depression, and other serious mental health problems have risen rapidly, particularly among women – getting the help you need gets harder.

In this gap comes content. And lots of it. Now, I’m sure the intention of most influencers is to help. But the problem is around the economics of influencing itself. People build social followings and then leverage that following to make money. In most cases, this is fine. In mental health, it is not.

While influencers in fashion or travel typically feed upon our desire for nice things, influencers who specialize in mental health feed upon our suffering to make money.

A multi-pronged problem 🔱

Now, it would be all too easy to point a finger at influencers for creating the conditions for exploitation. But in reality, they are just a more visible part of a broader problem.

While mental health awareness has never been higher, access to services has become increasingly strained. In England alone, two million people are on the waiting list for mental health services. Of those figures, nearly a million are children or young people.

In private mental health circles, the story is similar. I work at Headstrong Counselling, a national low-cost therapy service with more than 400 counsellors, and there’s a waiting list that at times is months long. This is then compounded by political rhetoric designed to demonize those who have been able to access health services.

All of this creates a vacuum for private, for-profit companies to step in to fill the void and fill the void they do. Through influencers, these brands buy their way into the trust and intimacy built between creators and followers and push services with questionable efficacy.

Influencers courted by big companies don’t have the time or capacity to vet the companies offering money for access. As a result, as is the case too often, consumers and their suffering are exploited.

But beyond this cottage industry, there is a bigger story about how capitalism has commoditized suffering.

Suffering is profitable 😭

We suffer. Sometimes we suffer a lot. This is a pretty consistent theme across human experience. Powerful people have exploited suffering to further their own causes for as long as there have been causes.

But in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, our capacity for suffering has been coupled with a new idea: that suffering is profitable. While health services try to cure or relieve someone of their symptoms, there is now what Professor and therapist Eric Greene calls a “mental health industrial complex” pulling in the opposite direction.

Just as with the military-industrial complex, the idea that companies cosy up to a country’s policy-making arm to ensure their interests are preserved, it can be said there is now a growing list of private, for-profit companies doing the same with our mental health.

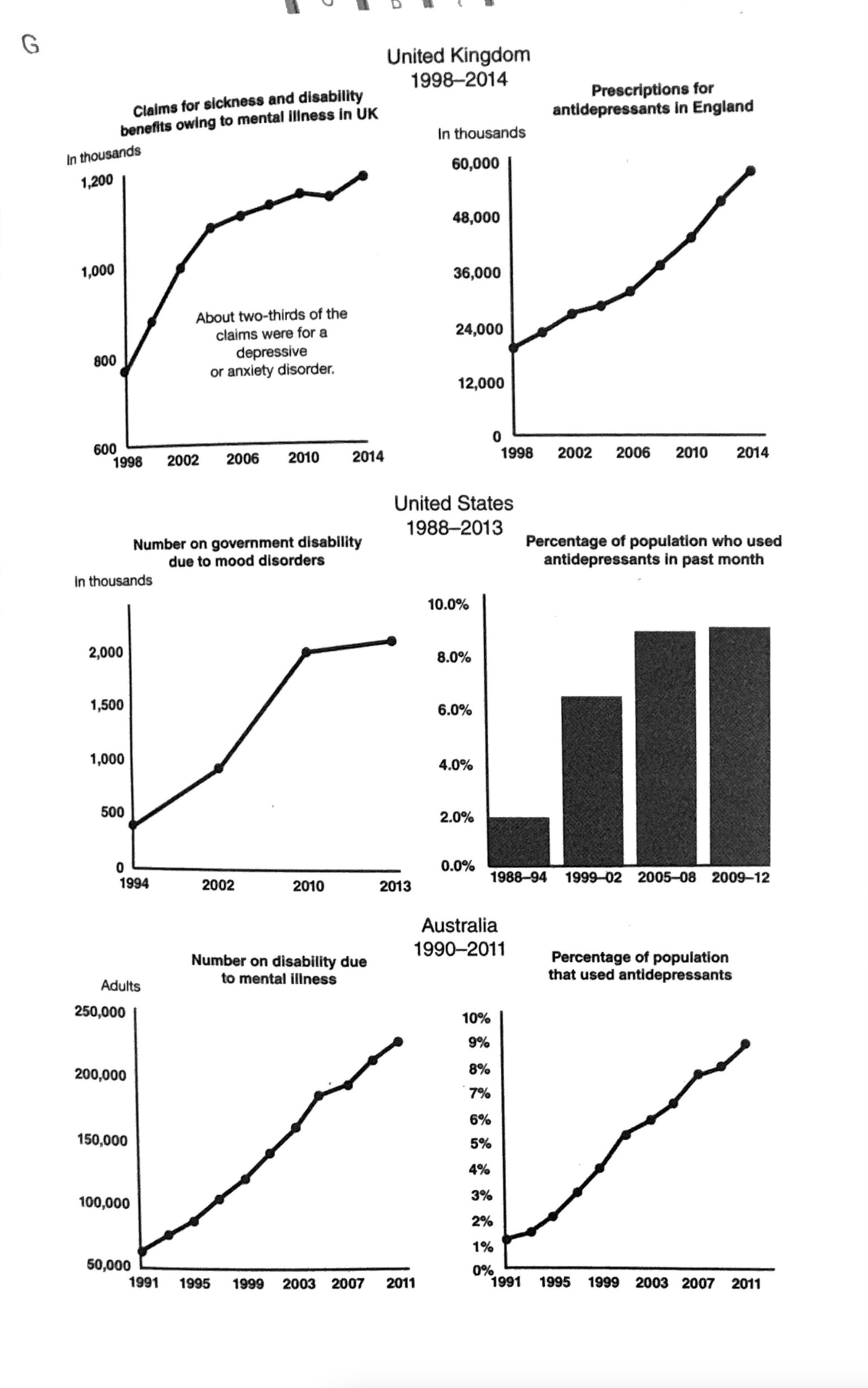

A case in point. With most illnesses and diseases, as awareness is raised, and research increases, our ability to treat and lower the rates of that illness improves. Look at things like survival rates for cancer, Covid, and even MRSA. We got better at treating it, survival rates have gone up, screening has got better etc.

Yet the opposite is happening in mental health. See the below charts from James Davies’ brilliant book Sedated: How Modern Capitalism Created Our Mental Health Crisis. And no, I don’t receive any money for recommending this book, it’s just really bloody good.

So what does this mean? Well, as I said earlier, influencers are the most visible part of a bigger problem. And that problem is it’s easier, and more profitable to keep someone where they are, then it is to do the hard work of listening, understanding, and collectively working to improve the lives of the many, not just the few.

A list of services - that I don’t make any money from 😭

Instead of my usual news roundup, here is a list of excellent mental health services that are vetted and regulated that I share with the therapists I teach:

- Hubofhope - A brilliant resource. Simply put in your postcode and it lists all the mental health services in your local area.

- Samaritans Directory - the Samaritans, so often overlooked for the work they do, has a directory of organisations that specialise in different forms of distress. From abuse to sexual identity, this is a great place to start if you’re looking for specific forms of help.

- Peer Support Groups - good relationships are one of the quickest ways to improving wellbeing. Rethink Mental Illness has a database of peer support groups across the UK.

I love you all. 💋