Is Mental Illness Contagious? 🧐

Here’s a puzzler for you.

We know that when you take the train in the morning, or go to an office, or a gym, or a library, whatever yanks yer daily chain, there is a chance you might ‘pick up’ something from another person. That could be anything from fashion tips to a cold or COVID, to something worse, like bad vibes.

We know and understand this idea well: it’s why we were all locked away for the best part of two years to protect the vulnerable. But while we know we can ‘catch’ physical illnesses from each other, have you ever wondered if we can catch psychological ones, too?

This is an idea I’m going to be diving into in this week’s Brink. An oft-overlooked corner of the world of psychology: mass psychogenic illness. Or what it’s more affectionately known as contagious mental health.

It all started in Hong Kong 🏙️

It was an unusually warm afternoon in Hong Kong back in November 1995. Local schools were emptying for the day.

A 14-year-old school girl Charlene Hsu Chi-Ying said goodbye to friends at St Paul’s Secondary School, an all-girls Catholic school, and started her walk home. It was the same as she had done every other day.

Moments later Chan Suk, a shop owner, was looking out of her window. She saw a painfully thin girl in a school uniform standing still on the edge of the road.

As she looked, a bus passed in front of her, blocking the girl from view. When it had passed, the girl had collapsed.

Chan Suk called an ambulance and ran across the road to help. By the time the ambulance had arrived, the girl was already dead. Police would later identify her as Charlene, a local girl from the Happy Valley part of the city.

The story instantly became front-page news.

John Saunders, a coroner was called to investigate what happened. While examining Charlene he was alarmed. She weighed just 75 pounds or 34 kilograms, the average 14-year-old weighs around 130 lbs or around 60 kilograms.

But worse than that, her heart weighed just three ounces, half the usual size for a girl of her age. Charlene’s body was so small, that many of the nurses in the hospital mistook Charlene’s body for a woman in her nineties.

During an inquest into Charlene’s death, John Saunders announced that Charlene had starved herself to death. Saunders told the inquiry she died of a disease that had never been seen in Hong Kong before. Anorexia nervosa.

People were shocked. What was this new disease that had arrived so suddenly that it killed a girl on the street? Journalists and analysts started looking. But while that was happening, other young women in Hong Kong had started showing the same symptoms.

By the end of the 1990s, some estimates suggest that 10 percent of young women in Hong Kong were suffering from anorexia.

But why? Why had it arrived, and why had it taken hold of Hong Kong’s young women?

High Hysteria 😱

What happened in Hong Kong is not unique. It’s an idea that has happened for hundreds of years: A mental illness suddenly turns up in a region or community without any prior warning. It’s turned up in the UK, parts of the Middle East, and southeast Asia. I’m going to explain more about that later.

But I want to go back to Hong Kong to help explain what exactly had happened. In Hong Kong, anorexia, as it was defined in the DSM or any other Western psychological manual didn’t really exist. It had its own local flavour.

The expert in that regionally specific form of anorexia was Dr. Sing Lee, a psychiatrist and researcher at the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

In the 1980s and 90s, he had been studying a rare and culturally specific form of anorexia in Hong Kong. Unlike American anorexics, most of his patients did not intentionally diet or express a fear of becoming fat. They complained about having bloated stomachs.

Lee would typically see two or three anorexic patients a year. After Charlene, it doubled, tripled, and climbed until he couldn’t handle the caseload alone.

But What happened?

To understand that, we need to go back to how Charlene’s death was reported. After she died, there was uproar in the press. A young schoolgirl dying on the street under such odd circumstances was bound to make headlines.

But as article after article was published, other questions emerged. Questions like, what was the meaning of this strange disease that led a bright, young, local girl to starve herself to death?

Well, It can be traced back to John Saunders, and his summary of why Charlene died. He had listed “anorexia nervosa” as the cause of death. But the term hadn’t been heard of much in Hong Kong.

Dr Lee had been studying a local version of it, but it hadn’t been talked about much in the press. So journalists went looking for experts who did understand this new and mysterious illness. Many of those experts were Western psychiatrists who had learned about the disorder while studying in Europe and the United States.

The definitions they had been taught suggested anorexia was “an intense fear of gaining weight or becoming fat” according to the DSM - the bible of mental illness. But that didn’t match Dr Lee’s understanding of it in his research. Local incidents weren’t about “fat phobia” as he called it, but about excessive bloating.

The Western definition was starting to squeeze out the local version. As the media attention intensified, so did the number of cases.

It’s important here to remember that before Charlene, cases of starvation were fairly rare. But afterward, they exploded. It started turning up in other schools across the city, and even universities. One college reported a twenty-five-fold increase in such disorders. But why? What was happening?

The story caught the attention of Ethan Watters, an American journalist who had been interested in understanding how culture affected the transmission and understanding of mental illness. He took a flight to Hong Kong and went straight to Dr Lee’s office.

Upon arrival, His first impression was maybe it had been there all along, and that the media attention allowed people to finally speak up about an experience they hadn’t publicized before. But if that was true, cases would have been documented in schools, and hospitals across Hong Kong. So Ethan went looking.

But found nothing.

Speaking to Dr, Lee he saw that rates of anorexia had stayed pretty flat in the last 10 years. So Watters came up with a theory: was the publicity of a disorder actually increasing its occurrence? If so, how did it work? The answer lay in an obscure French medical journal from the 1850s

Symptom Pooling 💊

In the mid-1800s, anorexia didn’t exist as a distinct medical category, according to historian Edward Shorter. Anorexia was considered part of hysteria.

This was a catch-all term that affected middle and upper-class women. But in 1873, French physician Ernest-Charles Lasegue concluded that self-starving deserved its own designation. Lasegue coined the term “anorexia nervosa”, and drew up a description of symptoms and a guide of how to treat it.

Lasegue published his work in prestigious medical journals at the time and gave talks up and down the country on his findings. But as he did that, cases of anorexia started to appear across France. Within ten years it had spread to London. One doctor based in the British capital said in 1888 that anorexia was now “a very common occurrence”.

Again it’s important to stress before it was labelled rates had been flat. But once psychiatrists had popularised it, it started to spread. This idea gives rise to a fascinating concept called “symptom pools”.

This is the idea that each culture possesses a set of symptoms that members of that culture would consciously and unconsciously choose to identify their distress. I’ll give you some examples.

- In southeast Asia, men experience something called Koro, a legitimate fear that their genitals are retreating inside their body.

- In Korea, menopausal women experience Hwabyeong, intense fits of sighing and heavy feelings in the chest, blurred vision, and sleeplessness.

- In the Middle East, there is Zār, a condition related to spirit-possession beliefs that entails dissociative episodes of laughing, shouting, and singing.

The history books are full of these examples. Here’s another one:

In the 1890s across Europe, men would fall into fugue states and walk hundreds of miles with no knowledge of their identities.

Also in the 19th century, a strange leg paralysis afflicted thousands of middle-class women which meant they could no longer walk or work.

Shorter’s work on symptom pools helped reveal the idea that symptoms and experiences of distress were fluid and culturally specific, meaning they changed from place to place.

Now, it’s important at this point to state that when people are starving themselves, they are going through genuine emotional distress. What they feel is real, and it’s something I’ve seen in my work as a therapist.

But what we are teasing out here is this idea that mental illness is shaped by the culture it lives in. Anne Harrington, Professor of History of Science at Harvard described this idea in better detail than I could:

“Our bodies are physiologically primed to be able to do this, for good reason, if we couldn’t we risk not being taken seriously or not being cared for - human beings seem to be invested with a developed capacity to mold their bodily experiences to the norms of their cultures, they learn the scripts about what kinds of things should be happening to them as they fall ill and about the things they should DO to feel better, and then they literally embody them.”

Interesting isn’t it? That there’s this adaptation at play. When we’re not feeling ourselves, we unconsciously find ways of expressing that to someone in a way they can understand and ultimately, help us heal from.

I’ll give you another example.

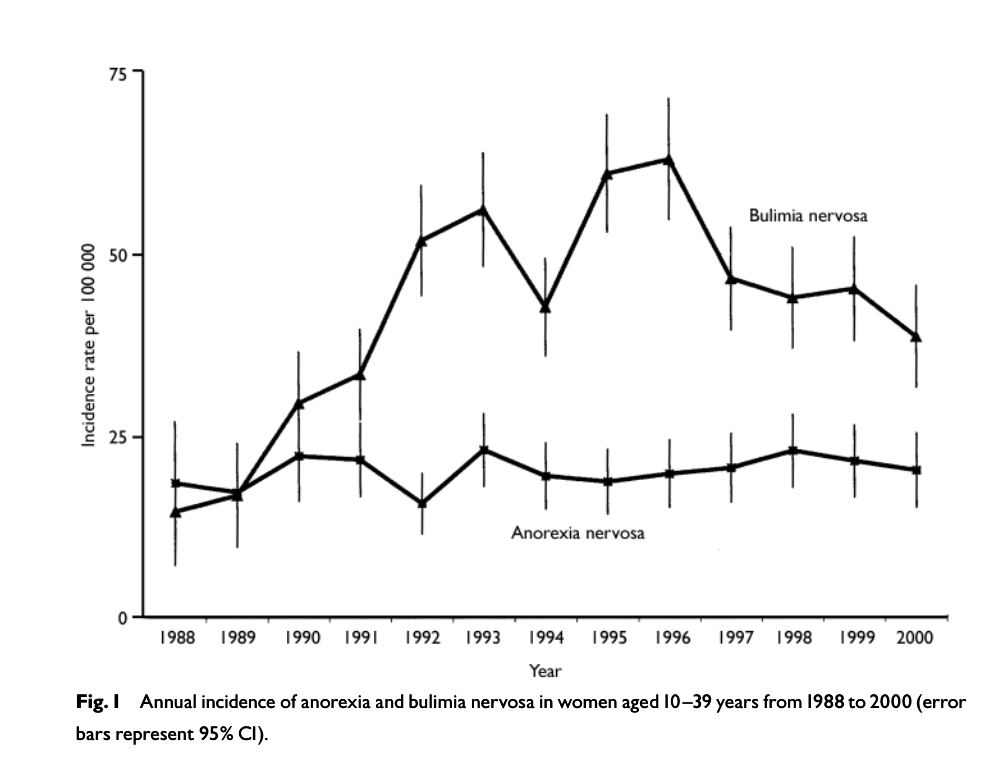

In the UK, British researchers studying eating disorders during the 1990s found the rate of bulimia among women exploded. But in 1997, it started to decline. Below is a horrendously dull-looking chart from a study on this idea.

When they looked at the data, they found something strange. Princess Diana had long struggled with the condition. In 1992, when rumours first emerged about her struggle, recorded rates went up. In 1994, when those rumours returned, rates rose once more. In 1995, Diana admitted that she had suffered from bulimia, and admission rates reached record highs.

But after her tragic death in 1997, the rates started to decline again.

Now it’s entirely possible that the raised awareness helped medical professionals get better at spotting this in patients, but another theory could be that the discussion of the symptoms and the idea of bulimia helped women in distress unconsciously embody the symptoms in order to get help.

I appreciate this may sound odd, but psychology has been studying this ‘bandwagon effect’ for years. Psychologist Solomon Asch has shown over and over again our tendency to conform to the group.

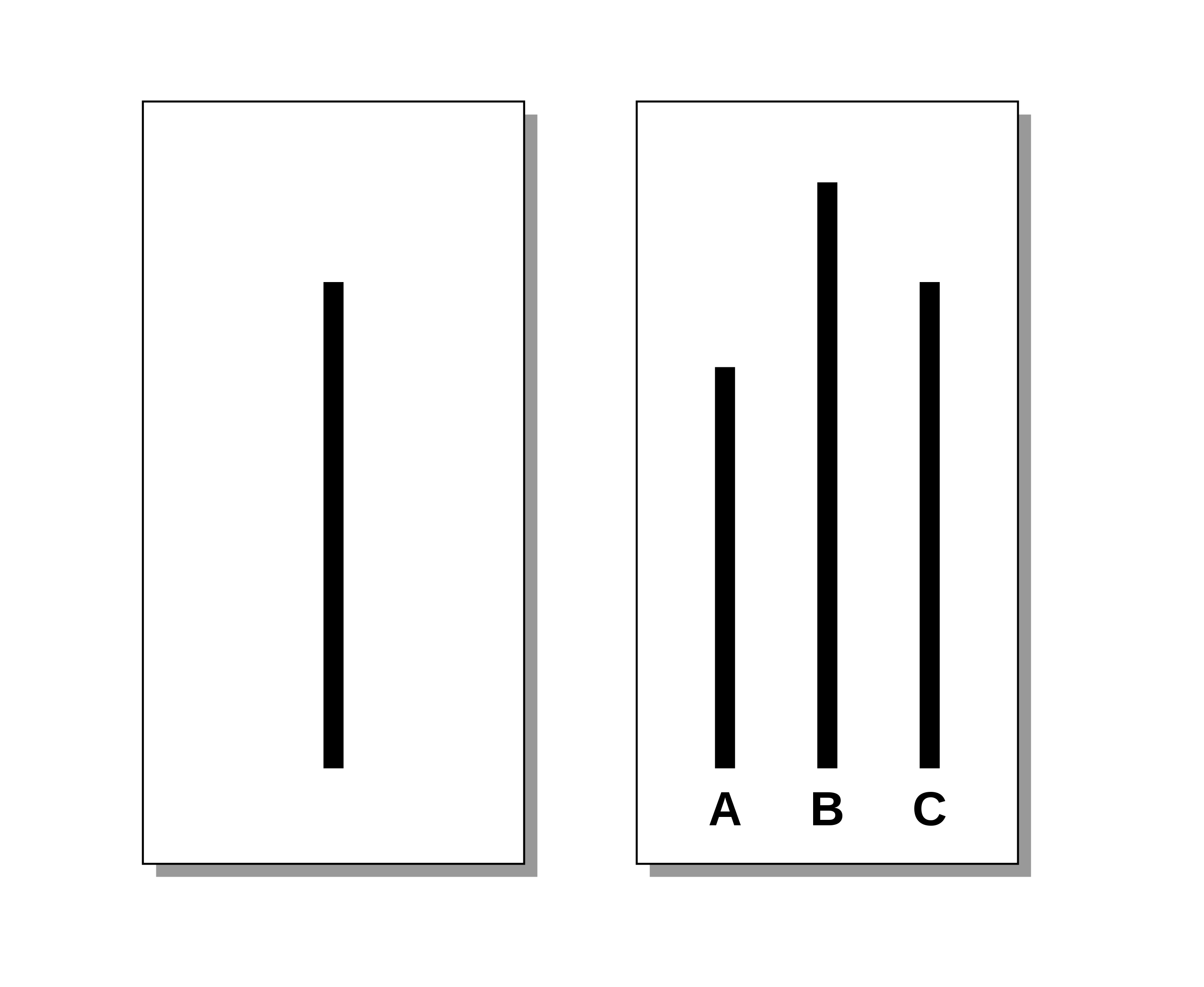

Take a look at the below:

In this experiment, people are asked to name which line on the right is most similar to the line on the left. If you’re watching this alone, you’ll confidently be able to say C. But in Asch’s experiments, he has people answer this question as a group. But with a twist.

The group surrounding the participant are all actors, and they all agree that a different line is the same, to see if this affected the participant's choice.

In Asch's tests, more than a third of the people agreed with the group, even though the group was clearly wrong.

Now imagine if you’re a person being told by powerful and influential groups that what you’re feeling is a new idea, even if it doesn’t quite fit with how you understand it.

This is what researchers believe happened in Hong Kong. A new symptom pool arrived, and young women started to identify with all the experts' descriptions of what was happening to them.

While Charlene died in 1994, the effects have continued. By 2007 about 90 percent of the anorexics Lee treated reported fat phobia, as opposed to the local version that fitted before.

So where does this leave us, and does it mean mental illness is contagious?

Seeing through a glass darkly 🔭

For more than a generation now, we in the West have aggressively spread our modern knowledge of mental illness around the world.

We have done this in the name of science, believing that our approaches reveal the biological basis of psychic suffering and dispel prescientific myths and harmful stigma.

But in doing that, we may have been teaching the rest of the world that illnesses take specific forms. We have been exporting our symptom pools across the world, in a strange psychological form of globalisation.

That is, we’ve been changing not only the treatments but also the expression of mental illness in other cultures. Indeed, a handful of mental health disorders — depression, PTSD, and anorexia — now appear to be spreading across cultures with the speed of contagious diseases.

So what can be learned from all of this? Culture shapes us in ways we’re only just starting to understand.

Of course, we can become psychologically unhinged for many reasons that are common to all, like personal traumas, social upheavals, or the loss of a loved one. But how we express those feelings, will shape how we experience, them and ultimately how we treat them.

Psychiatrists tell us that all mental illnesses, including depression, and PTSD. and even schizophrenia can be every bit as influenced by cultural beliefs and expectations today as we were when hysterical-leg paralysis or Zar took hold of local populations 100 years ago.

This does not mean that these illnesses and the pain associated with them are not real, or that sufferers deliberately shape their symptoms to fit a certain cultural niche.

What it does mean is mental illness is an illness of the mind and cannot be understood without understanding the ideas, habits, and predispositions of the mind that is its host.

Things we learned this week 🤓

- 🔪 Why we’re all so obsessed with serial killers.

- 💏 A new group is in town: super synchronizers. People who can align their responses to others instantly (bonus: it makes them more attractive).

- 🎶 There’s a weird link between music and intelligence.

- 🛢️ There’s a link between toxins and depression.

Just a list of proper mental health services I always recommend 💡

Here is a list of excellent mental health services that are vetted and regulated that I share with the therapists I teach:

- 💓 Hubofhope - A brilliant resource. Simply put in your postcode and it lists all the mental health services in your local area.

- 📝 Samaritans Directory - the Samaritans, so often overlooked for the work they do, has a directory of organisations that specialise in different forms of distress. From abuse to sexual identity, this is a great place to start if you’re looking for specific forms of help.

- 👨👨👦👦 Peer Support Groups - good relationships are one of the quickest ways to improve wellbeing. Rethink Mental Illness has a database of peer support groups across the UK.

I love you all. 💋