Conspirituality: How mindfulness, spirituality, and mistrust took over the web 💆

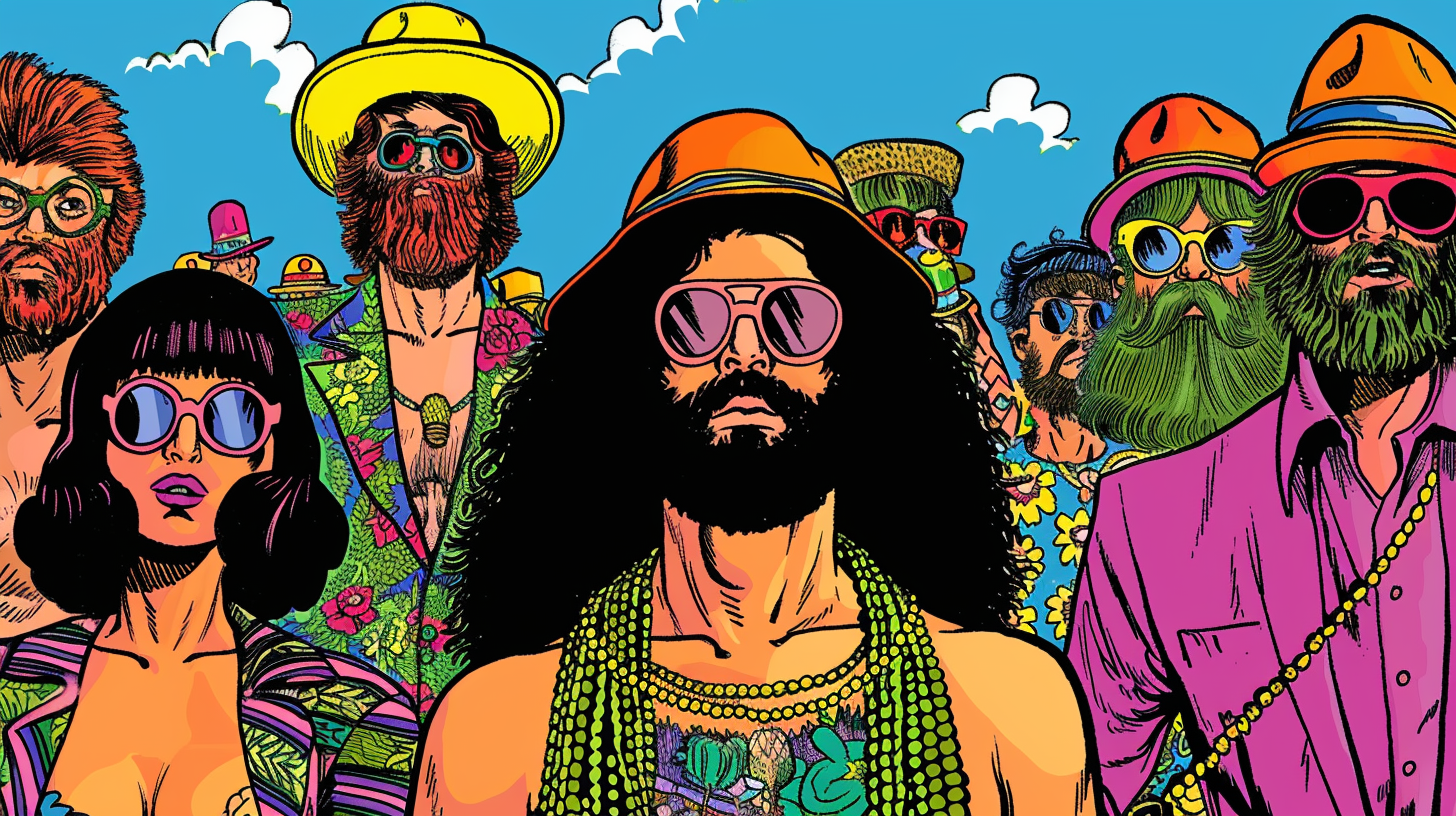

Dip into social media and you might find your favourite fitness/wellness/spirituality guru diverting from their usual soul-soothing content in favour of something a little left field.

It might be something around vaccines, or 5G, or the things found in food, or alternatively, an ‘herbal’ remedy that can cure diseases you’d normally find in hospital wards.

You might not have thought anything of it - it’s just the internet. But this peculiar mix of mindfulness, spirituality, and conspiracy theories has captivated the imagination of millions of people across the world.

The term that captures this smorgasbord of beliefs is called Conspirituality, and this week’s Brink is going to be how this strange mix of beliefs came to dominate the web.

Yoga bods 🙏

Conspirituality, as defined by the University of Essex, is an ideology fuelled by political disillusionment and the popularity of alternative worldviews.

Those worldviews tend to concentrate around two core beliefs:

- That a secret group of elites controls, or is trying to control the political and social order.

- Humanity is undergoing a paradigm shift in consciousness, requiring you to delve deep into spiritual beliefs to find the tools to survive the shift. You are essentially becoming one of the few who "get" what's happening and are taking action.

A perfect encapsulation (I apologise for using the word ‘perfect’ in the same sentence as this man) of these ideas would be Russell Brand. Littered in among his sermons on ice baths, trauma and healing, are ideas taken straight out of the QAnon playbook: Covid denialism, Russian disinformation, and the far-right-inspired “Great Reset” theory.

For younger audiences, the rise of figures like Shanin Blake on TikTok and Instagram sits in the conspirituality sweet spot.

What these two both have in common is that they preach mindfulness and “self-love”, but also a wide range of conspiracies ranging from the Covid hoax to 5G antennas secretly being used to control people and of course, the pyramids being built by aliens.

While it might be easy to mock these bizarre beliefs, they appear to have captured the imagination of millions of people. If you consider Brand and Blake alone, between them they have a reach in the tens of millions. There’s something in their peculiar mix that we want to believe in.

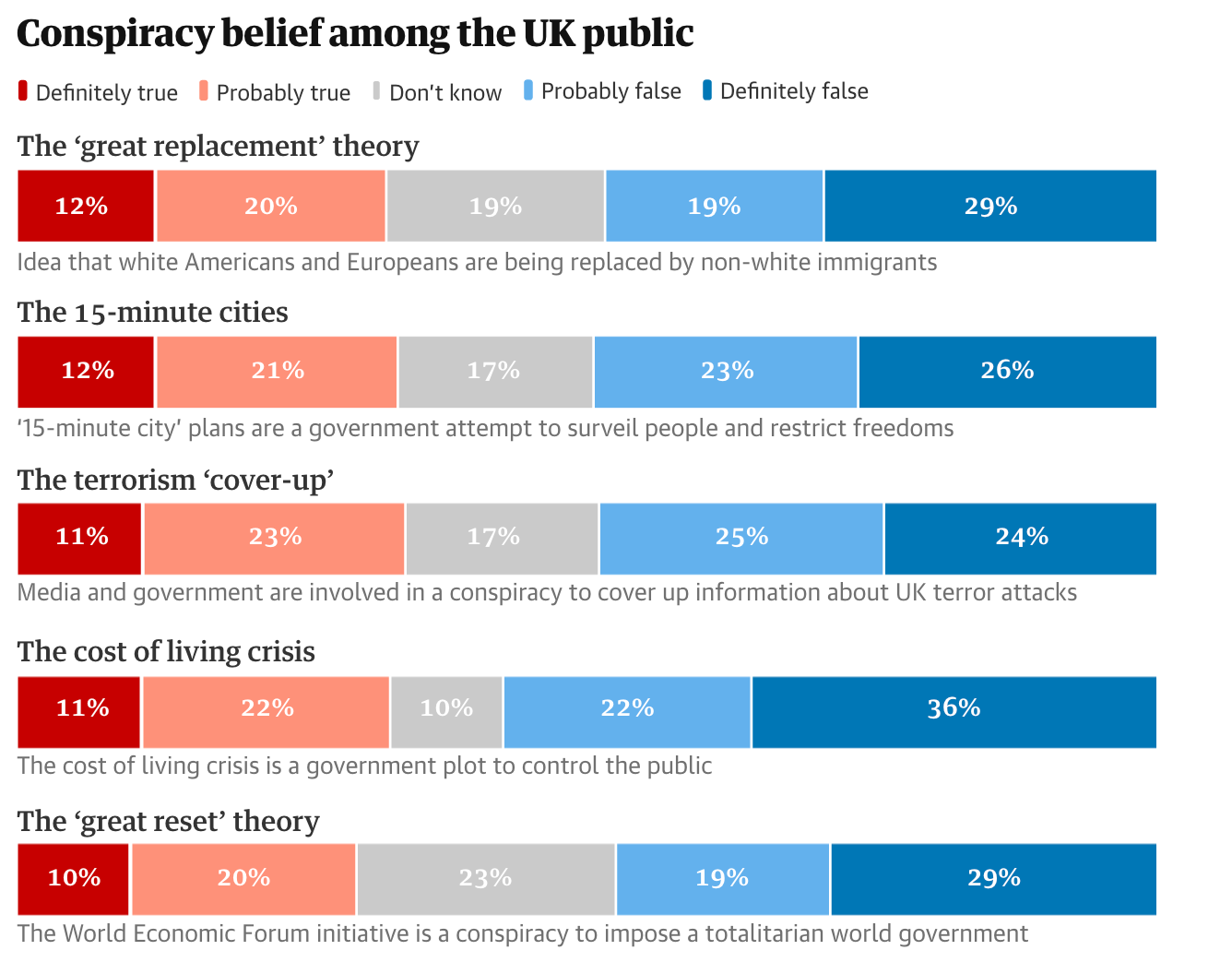

Indeed, some 25% of people in the UK believe Covid was a hoax, and more than 30% believe in the ‘great replacement’ theory and that the ‘great reset’ is happening right now.

What’s peculiar here is that these beliefs, traditionally the beliefs among the far right, have started turning up in yoga circles, and wellness communities.

Guru Jagat, a popular Kundalini yoga teacher invited QAnon conspiracy theorist Kerry Cassidy for an hour-long interview on YouTube.

The ‘QAnon shaman’ who stormed the Capitol on January 6, was revealed to be a yoga practitioner who is reportedly on an organic diet. There are even glimpses of it in our politics.

In America, Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., one of this year’s Presidential candidates, is one of the leading figures of the anti-vaccine movement. His director of messaging for the campaign is Charles Eisenstein, a New Age pundit who believed Covid was an opportunity for us to reject the “medicalized world” we live in. His first published book was called The Yoga of Eating.

As COVID abated, those conspiracists found new targets: climate change, veganism, and of course, gender and identity. This clash of what many thought were disparate worlds, has found a home on the internet and in our heads. But where did this idea come from?

Divine Intervention 🧘

It all started with the Nazis. Wait! Come back! I’m not comparing the people today to Nazis. I’m looking at the ideas, silly!

The Nazi party and Hitler himself held esoteric, mystical beliefs, alongside their, err… more terrible ones. The Nazi regime employed occultism throughout the war, recruiting astrologers and clairvoyants to provide military and diplomatic intelligence.

They also believed in things like the world ice theory, that events in the Bible and the destruction of Atlantis were caused by moons of ice hitting the Earth. Multiple Reich officials advocated Rudolf Steiner's occult-inspired (“biodynamic”) approach to agriculture, based on the moon and planets’ cosmic rhythms. And astrology and divination were used to obtain political insights and spread propaganda.

This itself, was built on an earlier idea popular in Germany and Austria before the Nazis called Ariosophy - which is a riff on Gnosticism This is the belief that there is a life force that pervades the universe and its mysteries could be grasped solely by people closely in tune with nature.

In Ariosophy, only the Ario-Germans were capable of this attunement since they were the most removed from modem rationalistic and materialistic society. The Jews, on the other hand, were viewed as a prime example of lower races since they were heavily involved in rationalism and materialism. Yoga was a part of curious idea, too.

While yoga as we know it today didn’t really appear until the early 2000s, in the 1920s, the Nazis were obsessed with it. German yoga teacher (and right-wing extremist) Mathias Tietke introduced yoga to Heinrich Himmler and helped fuse the idea that it could be used to “internally arm us to prepare us for forthcoming battles.” Indian mysticism fitted neatly alongside the belief that the Germans were part of a historical and spiritual race.

Thankfully the Nazis came and went. But their peculiar set of ideas endured.

New Order 🫡

After World War II, the New Age movement carried the torch of Western spirituality to a far bigger audience. While it jettisoned the systematic genocide part of the Nazi playbook, it continued to foster the idea that there were certain ‘truths’ that the mainstream did not want you to know.

These ideas were given greater power as scandals and stories of governments using their citizens for nefarious means began to grow. In America, stories of brainwashing and mind control by the CIA, paired with scandals like Watergate, fostered the idea that there might, indeed, be a secretive cabal of powerful people pulling the strings. That suspicion spread.

During the 1970s, Ann Wigmore, a holistic health practitioner and raw food advocate began promoting the idea that diseases, including cancer and HIV/AIDS, could be effectively treated with a raw food diet. Wigmore also believed that the pharmaceutical industry was part of a conspiracy to keep the population at large ill.

This idea sowed the seeds for a belief among conspiratorialist groups that big pharma is a secretive powerful force pulling the strings, and that the only response is to turn your back on mainstream ideas in favour of fringe beliefs. This idea was popular before the internet caught fire.

In 1998, a conspiracy theory spread that said vaccines make people autistic, In 2006, a Harpers Bazaar columnist claimed that the antiretroviral drug nevirapine was part of a conspiracy by the "scientific-medical complex" to spread toxic drugs.

A year before, American author Kevin Trudeau ignited debate around the issue with his self-published book Natural Cures "They" Don't Want You To Know About, cementing the relationship between a mistrust of institutions and a belief in ‘natural’ alternatives.

What we can start to see is that the tradition of spirituality and skepticism of everything else has been around for a long time. But it was COVID that supercharged these ideas, flinging them far and wide, giving birth to the conspiritualists we see today. But why are they so popular?

Uncertain times 😱

Jules Evans, a philosopher and research fellow at the Center for the History of the Emotions at Queen Mary, University of London, argues there’s a rhythm to these movements.

“There are certain moments in history when the collapse of the ruling narrative leads to a period of instability in what is believable and credible; when there's a collapse in the monopoly of meaning and lots of rival meanings and theories appear.”

Nazism - and its belief system - rose out of the Great Depression and the crippling reparations Germany was made to pay after World War I. The New Age movement appeared during the political turmoil of the 1960s and 70s. Conspirituality has emerged after the combined forces of the economic crash of 2008 and the Covid epidemic of the 2020s. Evans says there are other examples further back in history. The Reformation, for example.

The 16th-century revolt against the Catholic Church was spurred on by new technology: in particular the printing press. This enabled a breakdown of a monopoly in information. Suddenly people could print their own Bibles, read it, understand it, and come up with their own theories.

The result is that you had all kinds of different ecstatic and apocalyptic political movements rise up during the Reformation.

But steering it back to a more psychological focus for a moment, what we see during periods of great upheaval is a surge in uncertainty and fear.

The world doesn’t feel all that predictable and knowable, and the people in charge don’t seem to provide the answers we are looking for. When someone comes along that we trust and says, “You are being lied to, and there is another way” it’s appealing. This idea isn’t as far-fetched as the theories being peddled.

Our brains hate uncertainty and will look for anything that provides clarity, even if that clarity is not grounded in anything real. In the world of conspirituality that certainty tends to follow a familiar thread: everything is connected, nothing is as it seems and everything happens for a reason.

This can be the balm our sore heads are looking for. This framework is central to the messaging of wellness and New Age influencers, who link climate change to broader claims about government overreach and attacks on the ‘divine sovereignty’ of the individual. But while that might be soothing, what it really offers is a door to something far worse.

A different view 🌅

Life can, on regular occasions feel hard, and difficult and give off a faint whiff of glee when the world punches you in the face. And that’s before we get into wider societal challenges and of course climate change.

When someone comes along and tells us it’s because of a group of powerful people who aren’t like you, and are hell-bent on destroying your life as you know it, it can make us feel energised. We know what’s wrong, and we know who is responsible. Someone hand me my pitchfork.

But the problem with these ideas is, while they are energising, we need to ask ourselves why are we being energised? Are we being roused into action to change the world around us for the better? Or is our hate and fear being used for a different purpose? To buy something, perhaps? Or subscribe to someone’s oh so secret newsletter that will reveal the secrets to what’s ‘really happening’ for just $4.99 a month? Or maybe even to make us feel more isolated and alone? That around every corner is some monster looking to strip your life away in an instant?

Beneath these well-meaning influencers - who profit wildly from your fear - is a darker idea: you are alone, and the world is against you, but if you buy my crystal, my course, my yoga mat, you might, temporarily feel better. But I want to propose an alternate view. One that doesn’t require you to follow someone whose beliefs change according to where the money tree grows.

If we want to feel better, if we want to change the world, we have to look not to crystals, or how good our child’s pose is, or people on YouTube, but to each other.

The world is and can be shit. A lot of the time. But while the world seems massive, and these dark forces we keep being told about even bigger, the reality is, they live and die on how much you believe in them. If we can step out of our emotional bunkers and find others who want to make the world a better place, the power of these ideas diminish.

Conspirtualists want you to stay in your bunker, because their power only comes when people feel alone and trapped by powerful forces.

Maybe it’s time to start believing in something else. Maybe it's time we went outside.

Things we learned this week 🤓

- 🌲 On a mental health waiting list? Ecotherapy might help.

- 🌬️ Farting is suprisingly important for hormone production.

- 🧠 There’s a weird link between psychosis and being scratched by a cat.

- 🤷 Failure is overrated, say psychiatrists.

Just a list of proper mental health services I always recommend 💡

Instead of my usual news roundup, here is a list of excellent mental health services that are vetted and regulated that I share with the therapists I teach:

- 💓 Hubofhope - A brilliant resource. Simply put in your postcode and it lists all the mental health services in your local area.

- 📝 Samaritans Directory - the Samaritans, so often overlooked for the work they do, has a directory of organisations that specialise in different forms of distress. From abuse to sexual identity, this is a great place to start if you’re looking for specific forms of help.

- 👨👨👦👦 Peer Support Groups - good relationships are one of the quickest ways to improving wellbeing. Rethink Mental Illness has a database of peer support groups across the UK.

I love you all. 💋