Anger: The emotion no one knows what to do with 🤬

The world is an angry place right now. As I wrote about last week, the UK witnessed dozens of violent acts by groups claiming to be protesting an event that was distorted and twisted by known and unknown actors.

But zoom out a tad, and there has been anger on the streets in Argentina, India, France, Kashmir, Kenya, Bangladesh and more. Side note: these aren’t ‘equivalent’ protests, as in I’m not saying they are the same, more pointing out anger is everywhere.

The world - and of course, the internet - are awash with anger. Privately things are different. As individuals, we struggle with anger. But we see it a lot. It’s on our TVs, on our phones, and even in our offices.

Anger is les enfants terribles of our emotional world. It’s always with us in some form, but oh how we wish it didn’t have to be. But I want to try and take a different view in this week’s Brink.

Anger is useful. But for many of us, we see it as a destructive force that seems to hurt the people it touches. Redefining our relationship with being pissed off is, I argue, the key to healthier boundaries, and also a gateway to more subtle, harder to express feelings that don’t come so easily.

As a result, this week’s Brink is an ode to anger.

You won’t like it when I’m angry 😡

We see anger everywhere. A case in point:

- 45% of us regularly lose our temper at work

- 64% of Britons working in an office have had office rage.

- 38% of men are unhappy at work.

- 27% of nurses have been attacked at work.

- Up to 60% of all absences from work are caused by stress.

- 33% of Britons are not on speaking terms with their neighbours.

- 1 in 20 of us has had a fight with the person living next door.

- UK airlines reported 1,486 significant or serious acts of air rage in a year, a 59% increase over the previous year.

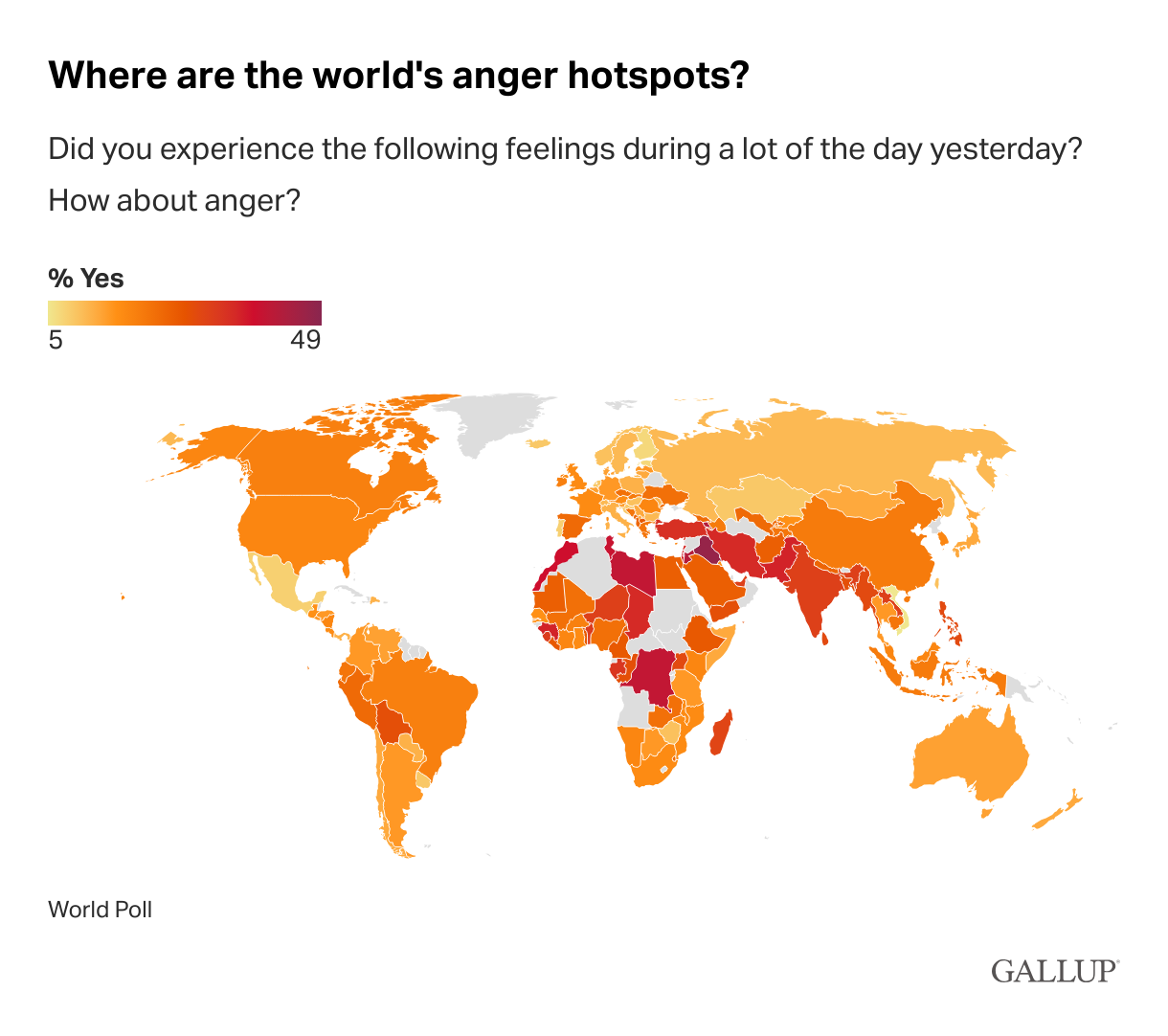

Gallup looked at the anger hotspots and found people have been steadily getting angrier since 2013.

But what is anger really? That might sound like one of those silly existential questions that can only be met with a giant eye roll, but it’s a relevant point to understanding why it gets such a bad wrap.

According to the Encyclopedia of Psychology, “Anger is an emotion characterized by antagonism toward someone or something you feel has deliberately done you wrong. Anger can be a good thing. It can give you a way to express negative feelings, for example, or motivate you to find solutions to problems. But excessive anger can cause problems. Increased blood pressure and other physical changes associated with anger make it difficult to think straight and harm your physical and mental health.”

The health problem is something we don’t hear much about. But it’s real. Chronic anger - or anger that we’re unable to manage or dissipate effectively - can lead to high blood pressure, and increased likelihood of a stroke and or heart attack, but also depression, anxiety and even eczema.

Suppressed anger has a long history with depression, first identified by Freud and talked about in psychological circles for more than a 100 years.

Anger also comes with a gendered component too. Women are more likely than men to express anger indirectly, whereas men are more likely to divert anger outwards.

Boys are often socialised to express anger openly, while girls are encouraged to suppress it. Those tropes continue into adulthood. The angry woman trope and the allure of aggressive men ideal help maintain those ideas throughout our lives. Of course, there are exceptions to these ideas, but it does help us understand that anger is more complicated than it seems.

But I’m going to make anger more complicated by adding in a different component: context. The context of where, when and how we express our anger makes it a harder emotion to know what to do with.

Reputation Re-assessed

There are certain places and spaces we all find anger easier to express than others. Driving a car is one of them. The reason we find our anger is more easily accessible - beyond the terrible driving of others - is the disconnect between the person we’re angry with and our anger.

A car or vehicle provides a barrier between us and the other, meaning our anger is freer to be expressed, but less likely to lead to confrontation. The internet captures this idea perfectly. You can sit in your living room and express your anger at pretty much anything you find without the same consequences if we did it in person.

That ease is also being seized upon by algorithms. A Yale University study found online networks encourage us to express more moral outrage over time. This is because expressing outrage online gets more likes than other interactions.

The increased number of likes and shares teach people to be angrier. In addition, these rewards had the greatest effect on users linked to politically moderate networks.

So we know what makes us angry, and how the loving machines of the internet are there to help us scream and shout at each other at any opportunity. But what doesn’t get talked about a lot is anger’s more positive sides.

According to science magazine Greater Good: “Research overwhelmingly indicates that feeling angry increases optimism, creativity, effective performance—and research suggests that expressing anger can lead to more successful negotiations, in life or on the job.”

In fact, anger has been linked with far more than that.

In one experiment, first published in 2009, sports scientists in the UK asked participants to imagine an intensely annoying scenario, before they underwent a test of leg strength, in which they were asked to kick as hard and as fast as they could for five minutes while a machine measured the force of their movements.

The anger led to a significant boost in their performance, as they channelled their frustration into the exercise, compared to participants who felt more neutral. Later studies found similar benefits in ball pitching, and jumping: the angrier they felt, the faster their pitch and the higher they jumped.

A burst of anger can also spark greater creativity. In brainstorming tasks, angry people come up with more original and varied solutions, compared to people who had been primed to feel sad or emotionally neutral. The increased arousal appears to super-charge the mind, allowing it to draw connections that are unavailable in other emotion states.

So if we know anger can be useful, how do we channel it more effectively? It’s all about how it’s applied, and by how much.

Everything in moderation

Anger, like my love of peanuts, is only useful in moderation. Giving free reign to anger, letting it boil over wherever and whenever doesn’t deliver the same benefits laid out above. Instead, it needs a partner, a vehicle that can be driven by anger to help it achieve its desired outcome: change.

When I work with clients I try to help them imagine anger as a ball of energy. Where we direct it is important, but what follows is perhaps the most important thing. So for example, let’s say someone treats you poorly at work. You get angry. You then direct that anger at that person. They notice. What do you want to happen next? What behaviour do you want to prevent from happening? What’s the message anger has helped you deliver? This I believe is the difference between useful and useless rage. If we can’t deliver the message we want to get across, anger becomes a bit headless. But we can learn to give our rage a head.

In recent research, a technique known as “psychological distancing” has proven to be particularly effective. This can involve imagining yourself looking back on the moment we became angry from a point in the future, or putting yourself in the shoes of a friend, and asking yourself how they might advise you to react.

Now, psychological distancing will not completely eliminate the feelings, but it can take the edge off your temper, and help you to make wiser decisions about the best way to respond. Even the simple act of talking to yourself in the third person (saying “David feels angry because…”) as if you are advising a friend, rather than yourself, has been shown to encourage a more constructive attitude to events.

It might sound mad, but anger needs another part of you to help it be heard, and help it become useful. Some therapists have found helping clients put their anger down on paper, or expressed in other creative means, can help clients create that space in their head where anger is not covering everything else we feel.

There will always be times when anger gets the better of us. After all, we can’t predict when we’ll be angry, but we can manage what happens after we feel it.

Anger isn’t the problem, it’s our belief that it can’t be anything more than a destructive force. Hopefully reading this you’ll see with a bit of practice, the opposite can be true.

Things we learned this week 🤓

- 💊 It’s official: serotonin has nothing to do with depression.

- 🙍 Good looking people believe they are more important.

- 👶 New study suggests people look like their names.

- 😴 There’s a weird link between your politics and how well you sleep.

Just a list of proper mental health services I always recommend 💡

Here is a list of excellent mental health services that are vetted and regulated that I share with the therapists I teach:

- 👨👨👦👦 Peer Support Groups - good relationships are one of the quickest ways to improve wellbeing. Rethink Mental Illness has a database of peer support groups across the UK.

- 📝 Samaritans Directory - the Samaritans, so often overlooked for the work they do, has a directory of organisations that specialise in different forms of distress. From abuse to sexual identity, this is a great place to start if you’re looking for specific forms of help.

- 💓 Hubofhope - A brilliant resource. Simply put in your postcode and it lists all the mental health services in your local area.

I love you all. 💋