A Brief History of Narcissism 📚

I was on the Tube the other day. As the train pulled into the station, normally those waiting to get on let passengers get off first. Except this time, that didn’t happen.

Instead of the usual huffing and tutting that makes travelling on UK transport a uniquely British affair, one person getting off the train shouted “You’re a narcissist!” to one particularly pushy passenger. And it got me thinking.

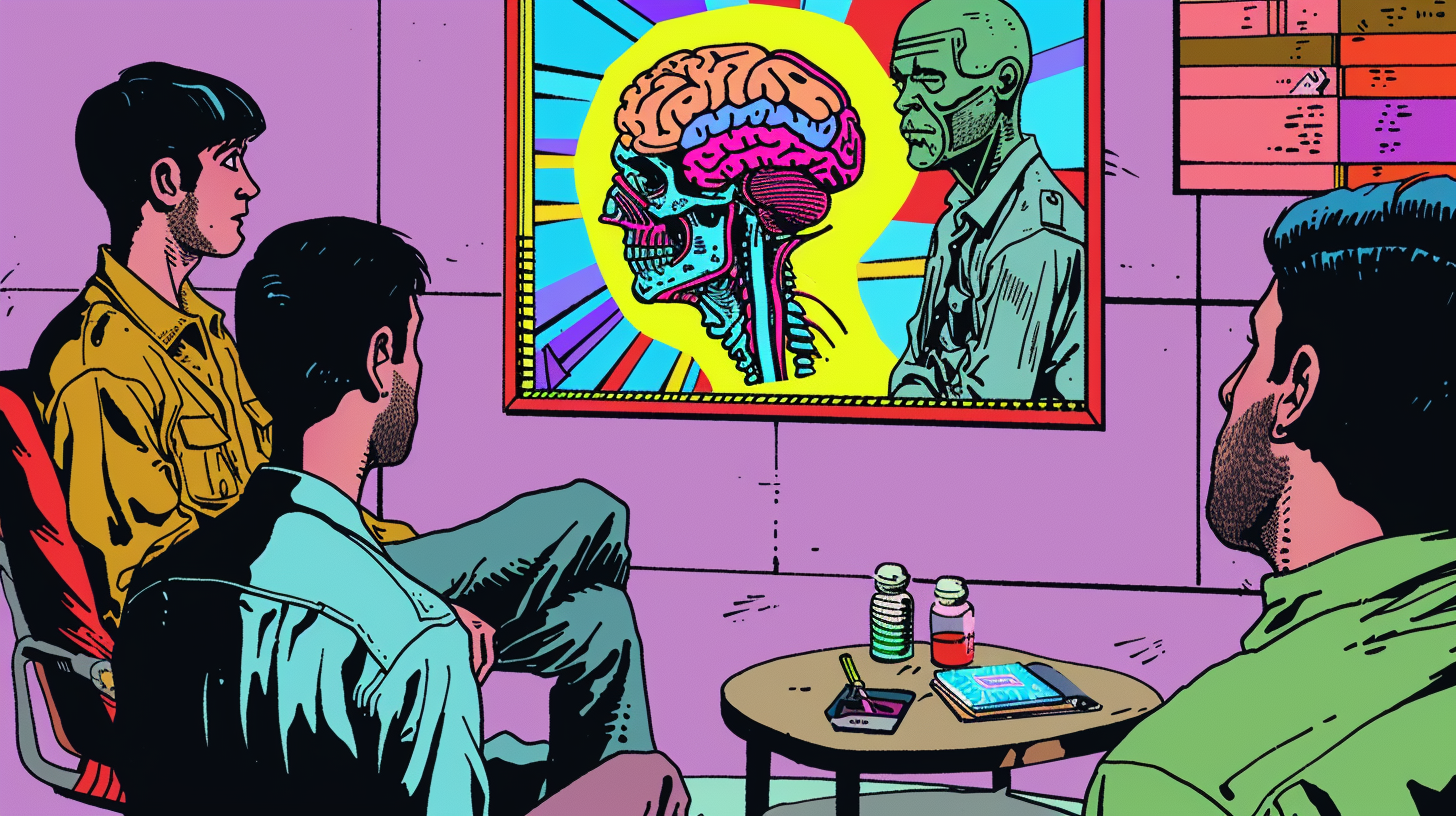

Narcissism is everywhere. There are more than 200 million posts that mention narcissism on TikTok. Those posts have been viewed nearly two billion times, and the term has even spawned its own sub-genre called NarcTok - which has more than 2 billion views.

Quora subgroups like All About Narcissists and Narcissistic Victims Syndrome Support abound, each boasting upwards of 80K followers. The Reddit community r/raisedbynarcissists has over 750K members.

We call our politicians narcissists, and we’re all too happy to dish out the same label to the people we work with, and even our partners. But why did an obscure character from Greek mythology - reinterpreted in the early 20th century as a type of personality flaw - become one of the most popular ideas of our age

And what if this label isn’t the panacea of labels we hoped it was?

Imma gana finda outa.

Greece is the word 🇬🇷

Before narcissism wandered into our lexicon for describing people we don’t particularly like, the idea came out of Greek mythology.

Narcissus was a good-looking lad who spurned the advances of a goddess called Echo. Being a goddess, rejection wasn’t an option. So the Gods made Narcissus fall in love with his own reflection in a pool of water. He would gaze at himself for so long, he ended up dying and becoming a flower. True story.

Why am I banging on about the Greeks? Well, one they’re great. But two, and more importantly for this story, I want you to pay attention to its origins. Narcissus came from the Greek version of a fairy tale. Essentially, it was a fantastical way of describing everyday life. I’ll come back to that idea later.

Anyway, narcissism, or rather, reference to the original Greek character, has been used throughout history - Byron and Baudelaire were both fans of the idea of ‘self love’ as they called it.

Over in psychological circles, they preferred the term ‘egotism’ to describe the idea behind self-absorption.

Fun fact: the word ego is another word derived from Greek. It means the “self” or “I”, and the word was popularised thanks to Mr. Sigmund Freud.

But the first whiff of the modern interpretation of narcissism didn’t arrive until 1898, when British sexologist Paul Nacke first used the term “narcismus” to refer to patients that treated the self as a sexual object.

A few years later, Otto Rank, an Austrian psychoanalyst and pal of Sigmund Freud, wrote a paper explicitly on this topic in 1911. It’s at this point we start to see some of the ideas that would make narcissism a household name.

Rank tied the term to vanity, and self-admiration, and later followers of Rank’s term would run with the idea and mix it in with another term “God Complex”. People in therapy rooms observed as having a God Complex were seen to be aloof, inaccessible, self-admiring, self-important, over-confident, exhibitionists and with fantasies of omnipotence. And so the term was born. But not quite as we know it today.

Much ado about nothing’ism 🤷

Therapists, psychoanalysts, and psychologists have been chatting about the idea of narcissism for more than 100 years.

When Freud wrote his influential paper, Narcissism: An Introduction in 1914, he saw it as a perfectly normal phase in the healthy development of children.

Others saw it in adults. Robert Wälder, an Austrian psychoanalyst, was the first to write a case study on the idea of someone having a narcissistic personality. But for most of the 20th century, it was discussed as a personality trait. Most saw it as a normal part of adult development, but there was uncertainty how it formed and what was responsible.

It wasn’t until the 1970s that it garnered the attention of the psychiatrists producing the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, or DSM-III to its friends. Published in 1974, it was the first time it was explicitly defined as a disorder, and distinctly different from Freud and others’ view that narcissism was a relatively normal thing.

It has its own checklist, and anyone having five of the nine traits, I’ve listed them below were destined to receive the label, “disordered”.

NPD is defined as comprising a pervasive pattern of grandiosity (in fantasy or behavior), a constant need for admiration, and a lack of empathy, beginning by early adulthood and present in a variety of contexts, as indicated by the presence of at least 5 of the following 9 criteria:

- A grandiose sense of self-importance

- A preoccupation with fantasies of unlimited success, power, brilliance, beauty, or ideal love

- A belief that he or she is special and unique and can only be understood by, or should associate with, other special or high-status people or institutions

- A need for excessive admiration

- A sense of entitlement

- Interpersonally exploitive behavior

- A lack of empathy

- Envy of others or a belief that others are envious of him or her

- A demonstration of arrogant and haughty behaviors or attitudes

So, how did you do?

While everyone was wondering out loud if they were narcissistic, psychiatrists like Otto Kernberg began wondering if genetics was responsible for narcissism (side note: it isn’t). Others jumped in, arguing that the condition was on the rise and that society was to blame.

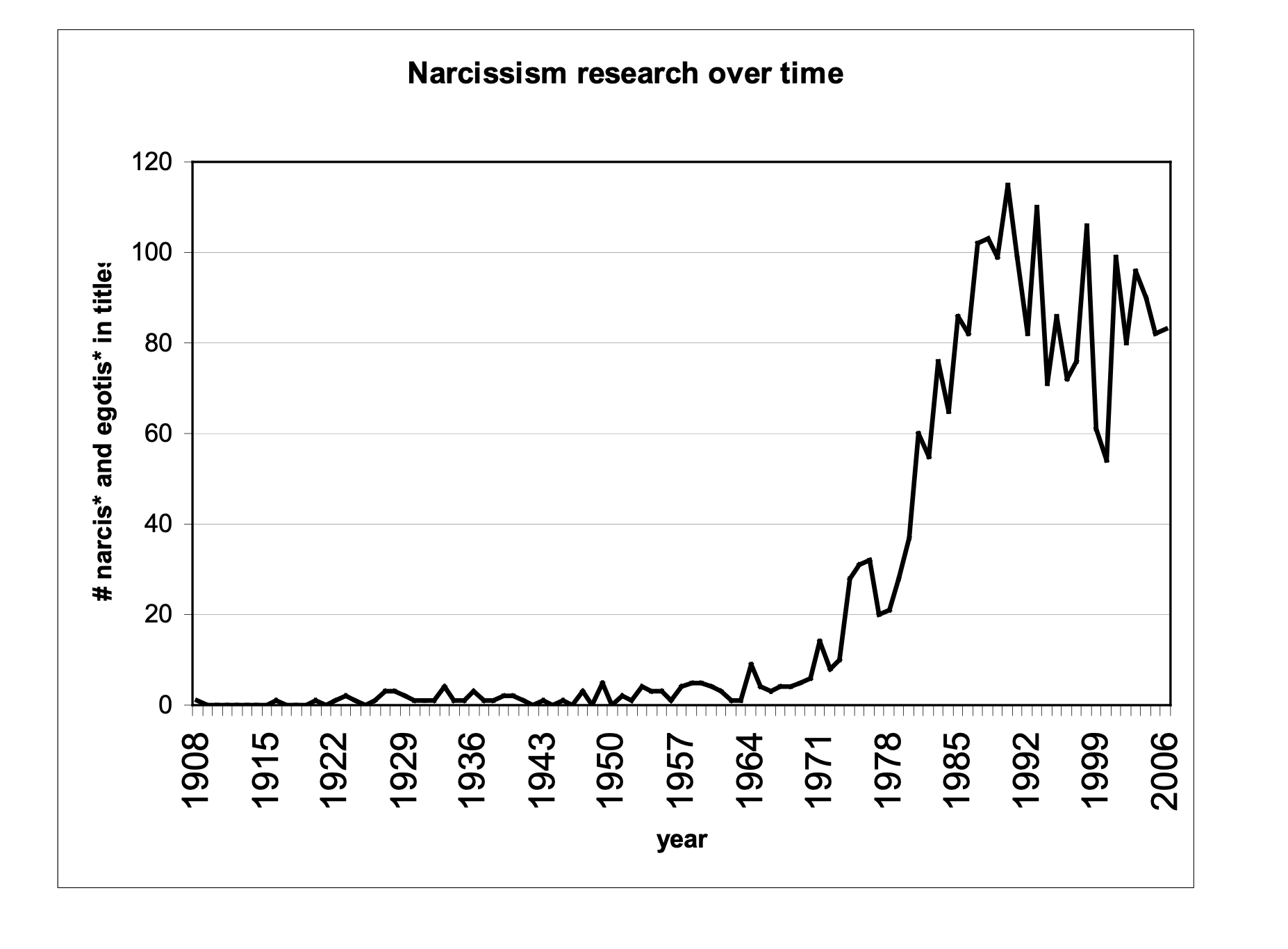

This led to an explosion of research into what was now considered a disorder. Not to mention a list of new drugs that would be used to treat it.

But the rates of Narcissism remained tiny. Even today, in our trigger-happy labelling era, it’s surprisingly difficult to find someone with diagnosed NPD. While some studies have found as many as 6% of Americans have it, other studies with more stringent criteria couldn’t find any.

But yet, go and look online and everyone is frantically trying to diagnose themselves or diagnose others. What’s going on? Well, as always, it’s more nuanced than you think.

Therapy Speak 🤐

I’ve written many times on the rise of “therapy speak”, a slightly silly catch-all term for words that have historically lived in the realm of mental health circles and found new homes elsewhere.

During the pre-war years, terms like “hysteria,” “shell shock,” and one’s “inner child” all crept off the couches of Sigmund Freud and his contemporaries into our lives. Ideas around “repressing feelings”, having a “death wish”, “slips of the tongue” and “transference”, came a bit later. But all were born and raised by people working in the mental health field.

More recently, there’s been a new wave of terms. Now we talk about our coping mechanisms. We project or are projected on to. We shun “toxic” people. We catastrophize and ruminate.

We diagnose, or are diagnosed: OCD, depression, anxiety, ADHD, and narcissism.

We make, break or struggle to “hold” boundaries. We practise self-care. We know how to spot gaslighting. We’re tuned into our emotional labour. We’re triggered. We’re processing our trauma. We’re doing the work.

But in reaching for what feel like helpful labels to understand what’s happening to us and others, it also does other things.

Terms like “boundaries” and “holding space” have created an odd dynamic where interpersonal relationships can be treated in more transactional ways. Therapy speak meant we became further apart, rather than closer together. Here are some other examples I’ve heard recently:

- your intrusive neighbor has “borderline personality disorder”

- Your best friend gaslit you because you didn’t want to go out.

- Your mother is a narcissist because she ignored you when you came home.

These things might be true. But what happens when we do that is that we get a sense of authority and power, while pathologising someone else. In essence, when we reduce or boil someone down, it makes us feel ‘right’ and the other ‘wrong’. These words effectively become clubs that strip others and our experiences of their complexity.

It transforms a “deeply relational, nuanced, contextual process,” says Lori Gottlieb, the author of the book Maybe You Should Talk to Someone, into something “ego-directed, as if the point were always, ‘I’m the most important person and I need to take care of myself.’ ”

Narcissism has become a way we do that. We can label someone a narcissist and feel good about it. We called out their behaviour using a term that gives our knee-jerk response moral authority. But once we've done that, what happens then?

“Therapy speak offers an odd way of relating to one another,” says Eleanor Morgan, author of Hormonal: A Conversation About Women’s Bodies, Mental Health and Why We Need to Be Heard. “It prizes disconnection over the messy ebb and flow of real life. It’s rife, yes, but let’s not pretend that actual therapy is at the crux of it.”

The use of official-sounding language makes us feel good, but leaves us alone and further from what we want: togetherness and understanding.

In essence, Narcissism arose out of a desire to know more about the person staring back at us. But in our quest to know more, we're understanding less.

Things we learned this week 🤓

- 🤣 Want to be more likable? Use more facial expressions, says study.

- 🌬️ A study looks at how your sense of humour changes as you age.

- 👨💼 Longest study of hybrid working finds it’s good for people and doesn’t damage performance.

- 🎥 A good film on the BBC looks at why suicide remains the biggest killer of men under 50.

Just a list of proper mental health services I always recommend 💡

Instead of my usual news roundup, here is a list of excellent mental health services that are vetted and regulated that I share with the therapists I teach:

- 💓 Hubofhope - A brilliant resource. Simply put in your postcode and it lists all the mental health services in your local area.

- 📝 Samaritans Directory - the Samaritans, so often overlooked for the work they do, has a directory of organisations that specialise in different forms of distress. From abuse to sexual identity, this is a great place to start if you’re looking for specific forms of help.

- 👨👨👦👦 Peer Support Groups - good relationships are one of the quickest ways to improve wellbeing. Rethink Mental Illness has a database of peer support groups across the UK.

I love you all. 💋