A Brief History of Imposter Syndrome 📚

Imposter Syndrome, it’s everywhere. It’s in our schools, our colleges, our workplaces, and even in our relationships. In a review of 62 studies on the subject, wherever we looked, between 56-82% of people say they had it or are currently experiencing it.

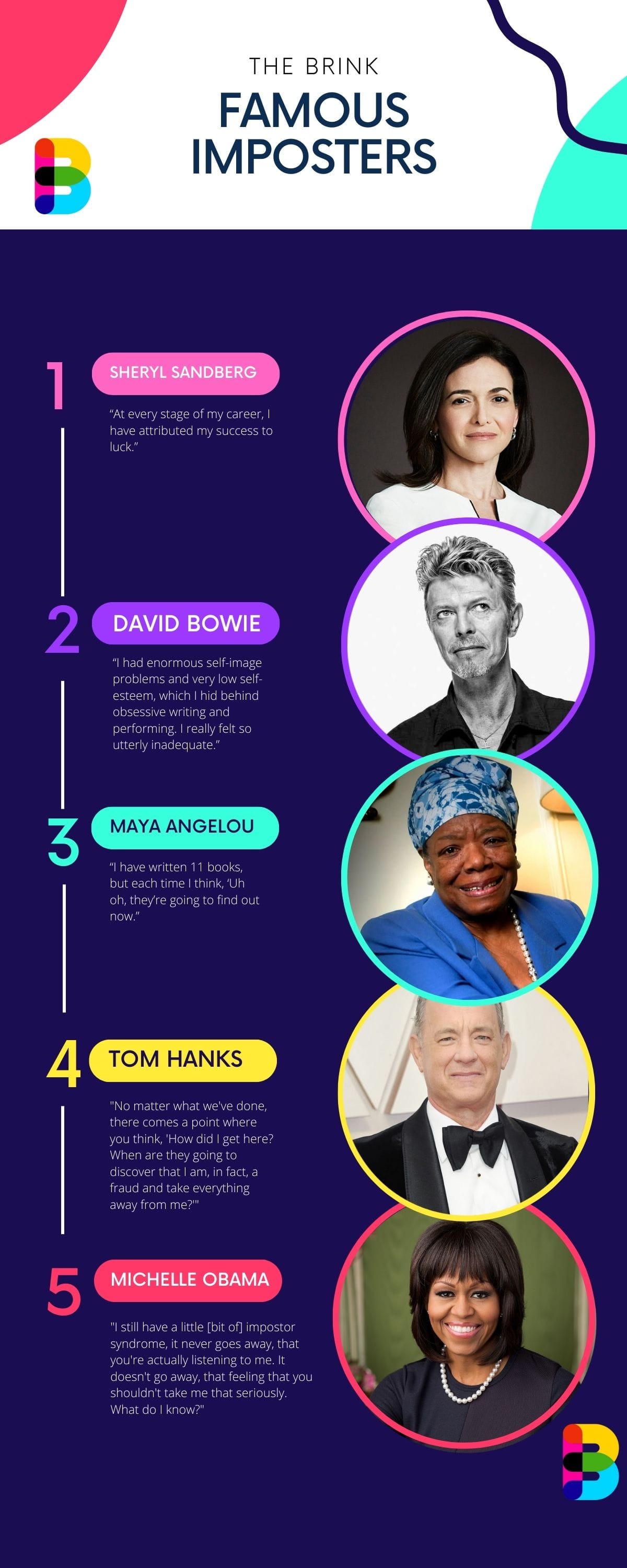

And it’s not just us regular people, either. Some of my favorite musicians and actors have reported feelings of impostorism:

I’ve even made a lovely little infographic which you can find below. As a result, it’s developed its own cottage industry of books, seminars, and of course, super-duper-easy-fun-sexy-cool TikTok videos. So it’s high time I dedicate 800-1200 words talking about where it comes from, and how it’s evolved and changed with time. But more importantly, I’m going to be heading back to the two women who created it and ask, “Does the label empower us or just hold us back?”

Imposter Origins 🕵️♀️

Imposter Syndrome was first coined by psychologists Pauline Clance and Suzanne Imes in 1978. They wrote a paper called “The Imposter Phenomenon in High Achieving Women”, which was later shortened to the far more catchy “imposter syndrome” we know and love today.

In the original paper, which came about after the authors spent time talking to more than 100 capable women working in academia, described the idea as “an internal experience of intellectual phoniness. Imposters are ambitious, hard-working people who believe they must have fooled anyone who thinks they are capable or talented.”

Even when faced with objective evidence of their skills, said Clance and Imes, they remain unwavering in their conviction that they succeeded thanks to luck or error.

The more plentiful their accolades, says the paper, the more anxious they are that they’ll be found out. If they do fail, they see it as ultimate proof that their success was somehow undeserved. Clance and Imes described the cycle that impostor feelings often produce. It goes something like this:

- As a sense of impending failure

- This leads to a period of frenzied hard work

- Which provides gratification but it is short-lived.

- A temporary feeling that failure is kept at bay is replaced by the old conviction that failure is imminent.

Clance and Imes were keen to point out, however, that it wasn’t a syndrome in the sense of what we see in medical textbooks. It doesn’t feature the requisite three of the “four Ds” of mental illness definition: deviance, distress, dysfunction, and danger.

But nevertheless, after the paper was released it became an instant hit - if academic papers could be such a thing. Clance told the New Yorker that she had so many requests for the paper she spent most evenings photocopying the thing.

Today the term has left the confines of women in academia and is now experienced by men and women everywhere. As a result, debate has ensued over its proper usage. How it was first defined, how it is applied, whether men can be allowed to feel the same feelings, and of course, how the idea applies when looked at through a lens such as race and history.

There’s a great summary of all of this over on Harvard Business Review. But for now, I’m sticking to how it traveled beyond what Clance and Imes first believed to be used for, and how it could be combated in the first place. More on that later.

Breaking the cycle 💥

So as Imposter Syndrome galivanted across the world, turning up in the boardrooms and bedrooms of the world, the question on everyone’s lips was, “So how do I treat the bloody thing?”

Repeated successes usually don’t break the cycle, said Clance and Imes. All the frenzied efforts that are directed into preventing the discovery of one’s inadequacy and fraudulence - also known as more achievement - ultimately just reinforce the belief in this inadequate, fraudulent version of the self.

In a follow-up paper to the original released in 1985, Clance explained that the following six characteristics can distinguish the impostor phenomenon. To have it, Clance said you had to experience at least two of the following:

- The impostor cycle

- The need to be special or the best

- Characteristics of superman/superwoman

- Fear of failure

- Denial of ability and discounting praise

- Feeling fear and guilt about success

She even developed a scale if you’re interested. But as the authors tried to satisfy the need for answers from the world, so the meaning and purpose of the label began to change. People started to use the imposter phenomenon as a way of pathologizing their experience. Meaning, that once a label could be used to encapsulate how they felt, it became an identity all of its own.

Clance and Ames were keen to point out that imposter syndrome is an experience a person has, not a mental disorder. But for many of us looking for answers to our discontent, it was a useful byword that allowed others to easily understand what we were feeling: uneasy with the world we found ourselves in. So we ran with it.

But in doing so, we come to believe that it is something that cannot be resolved. An immovable object in our identity that we need to make constant room for. This was amplified by what Clance and Ames found: that sufferers didn’t see it as worthy of the attention of a trained professional, and often chose to soldier on alone. But is it? And more importantly, where does it come from?

False selves 😶🌫️

When the paper was first released, there wasn’t a great deal of research into its origins, but more recently, researchers believe a key can be found in our childhood. Oh yes. Did you honestly think I could go one newsletter without talking about childhood? You are so wrong my friend.

Many theories use different language to describe it, but the key idea in all of them is that: at some point along the way, you had what would be called a keystone relationship that created certain conditions. Typically those conditions were along the lines of: I will only love you, accept you, be nice to you, or tolerate you if you meet certain conditions.

This idea replaces what was (hopefully) originally there, which was that you are inherently worthy. Instead, you see belonging and attachment to others based upon what you can provide them, rather than who you are.

This kernel idea grows with time, and starts to mingle with other parts of ourselves: most commonly in places and spaces where we discover that our actions can lead to affirmation: think education, work, or even relationships. These spaces then become battlegrounds. We’re pursuing a fantasy that says, “This person, this achievement, this accolade will heal me, but only if I perform in exactly the way they want it”. But sadly, we never seem to get there.

This fantasy gets lost in our subconscious and we find ourselves flogging ourselves without really knowing why. But there is a why, if you’re willing to look for it.

A talking cure 🤐

Remember when I said earlier that people didn’t deem feelings of imposter syndrome worthy of attention so carry on alone? Well, the cure comes by asking for help. And by asking for help I don’t mean posting a tearful Instagram video. I mean asking the people that matter in our lives for time and support.

SIDE RANT: Broadcasting your feelings is not the same as exploring them in a safe, trusting environment. Please stop commoditizing how you feel.

Clance and Ames found sufferers were healed not by more success, or more drive, or by more determination, but by resonating with others who felt the same. The authors found group therapy was the most powerful way of helping sufferers put their feelings into perspective.

The reason? We get to see the inner workings of other people and see that we're not alone in our suffering. Which can help us soothe those parts of us that feel out of place. And there’s mounting evidence to support that.

While that may not be available to some people, I’d like to suggest another way we might think about approaching it. I’m going to use a broad brush, but our identity is essentially made up of three overlapping ideas:

- How we experience ourselves

- How we present ourselves to the world

- How the world reflects that self back to us

Imposter Syndrome is, in a way, really about a disconnect between these three ideas. For us to feel congruent, a fancy therapy term meaning when all parts of ourselves align, there needs to be an agreement across all three of those parts that make up who we feel we are.

Imposter syndrome is really just a way of saying, “My parts don’t agree with each other.” And this is fine. Actually, I’d say this is more than fine. More than 90% of the clients I have seen and see report exactly this experience: that inside us are competing factions or parts that see and believe different things. This isn’t a syndrome, it’s part of being a person.

And part of being a person is learning to live inside our own skin. Even when it feels like we’re locked inside a Hunger Games-esq Battle Royale bloodbath between all the competing ideas that live inside us. Imposter syndrome is really a way of telling ourselves that we don’t belong here.

But, if we can find a way of listening to those parts that say I don’t belong, or I’m a fraud, what we might find is that they’re really just trying to look after us. They’ve just developed a really odd way of telling us. No one wants to feel rejected, undeserving, or unworthy. Those parts are just trying to protect us from moments where that might happen. But in reality, 99.9% of the time, nothing happens. And the 0.1% of the time it does? We can survive it.

If we can give ourselves that space to understand these protective forces inside us, we can also help them realize that we’re doing just fine as we are.

Things we learned this week 🤓

- 👰♀️ When couples divorce later in life, women find it harder to bounce back than men.

- 🤷 Compassion fatigue is real.

- 🕹️ Virtual reality is being used to treat anxiety in young people, and it’s working.

- 💑It’s official: opposites do not attract.

If you would be so kind 🙏

I am terrible at marketing. Literally terrible. But I’m trying to get better, and I need your help!

If you enjoy my witterings, please do share with someone or subscribe, it really helps.

I love you all. 💋